FPP spoke via email with author Olivia Kate Cerrone about the silence surrounding child slavery in Sicily, the powerful stories that haunt her as a writer, and so much more. Read Cerrone’s interview then plan to her read on Tuesday, September 12th at Silvana (116th & Frederick Douglass) in Harlem.

FPP spoke via email with author Olivia Kate Cerrone about the silence surrounding child slavery in Sicily, the powerful stories that haunt her as a writer, and so much more. Read Cerrone’s interview then plan to her read on Tuesday, September 12th at Silvana (116th & Frederick Douglass) in Harlem.

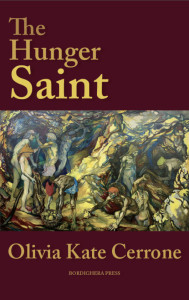

In your novella The Hunger Saint, you write about soccorso morto, a child slavery system once practiced in Sicily. Was there a particular fact, image, or story that pushed you to go deeper with your research and write this story?

The ages of the children (some as young as five and six years old) when they were first forced into a life of hard labor in the sulfur mines disturbed me the most. I was desperate to understand what could drive a family, let alone a society, to engage in and normalize such a brutal practice. Of course, the tragic presence of child slavery, the exploitation rooted in severe poverty and lack of labor laws or legal protection, is not exactly new, and continues throughout the world today. Perhaps it was also the fact that the carusi were never spoken about, and had become largely forgotten among most people, that drove me to delve into research and write the book.

I discovered the carusi largely by accident, while taking a Sicilian language class to gain a more intimate connection to my own sense of identity. Booker T. Washington’s description about the carusi also haunted me. He also visited the mines in Sicily to witness the child laborers for himself, as part of the research for his sociological book The Man Farthest Down: A Record of Observation and Study in Europe. Washington compared the suffering of the carusi to that of African-American slaves: “the cruelties to which the child slaves have been subjected…are as bad as anything that was ever reported of the cruelties of Negro slavery. These boy slaves were frequently beaten…in order to wring from their overburdened bodies the last drop of strength they had in them.”

I discovered the carusi largely by accident, while taking a Sicilian language class to gain a more intimate connection to my own sense of identity. Booker T. Washington’s description about the carusi also haunted me. He also visited the mines in Sicily to witness the child laborers for himself, as part of the research for his sociological book The Man Farthest Down: A Record of Observation and Study in Europe. Washington compared the suffering of the carusi to that of African-American slaves: “the cruelties to which the child slaves have been subjected…are as bad as anything that was ever reported of the cruelties of Negro slavery. These boy slaves were frequently beaten…in order to wring from their overburdened bodies the last drop of strength they had in them.”

I was driven to create a compelling story, one rooted in hope and survival, that shed some greater light and awareness to this history, while examining how systemic oppression within a corrupt society can distort and limit the greater humanity of its citizens, fostering suffering and cruelties against its most vulnerable members.

The Historical Novel Society calls your writing “lucid, precise, often lyrical when describing Ntoni’s world.” Do you feel there’s anything that particularly prepared you to create this world? Any writing before, or personal connection?

The most powerful stories are those that haunt us. It’s those felt-life details that get under our skin and leave a lasting impression. In my fiction, I strive to craft compelling narratives that also work to engage readers on a sensory level too, absorbing them in a character’s very specific experience of being that allows for greater nuance and complexity to be expressed. Anthony Doerr, Toni Morrison and Alice Munro are authors I am constantly rereading and learning from in this capacity. Richard Wright’s Native Son, Lisa Ko’s The Leavers, and José Saramago’s Blindness are books that continue to haunt me for these reasons.

In your recent The Rumpus interview, you said that as a writer, you are “very interested in trauma…that’s where the story lives.” Could you tell us more about what this approach has meant for your work?

I write to understanding suffering that is essentially rooted in social oppression and discrimination. Fiction can be a very powerful means of creating a deeper, more compassionate awareness and insight into complex and difficult realities that work to polarize and alienate people both politically and emotionally. Individual trauma so often reflects the injustice and oppression within a society on a larger scale. It is said that “the path to the universal runs through the individual.” I am driven to produce fiction that speak to larger issues of human rights, identity and belonging. Right now, I’m working on DISPLACED, a contemporary novel set in Boston that questions what it means to be an American in a time fraught with political and social tensions over current immigration policies, living undocumented, rampant fear, and discrimination. The novel also wrestles with themes of exploitation, homelessness, and deportation.

What urgent advice would you offer emerging writers?

Never give up. Read widely to understand what great writing looks like on the page, from sentence-level to scene, and how compelling novels are crafted together. Keep revising your work and striving to achieve greater clarity and deeper nuance through the stories and characters you bring to light. Root yourself in this work and keep going, no matter the rejection or the disappointment. Every “no” is closer to a “yes.”

Author photo credit: Ashley Inguanta