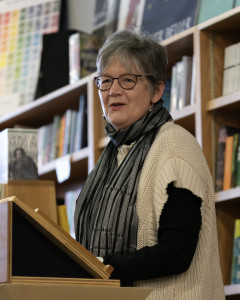

In this 2021 FPP interview with Dr. Terry Bohnhorst Blackhawk, Bohnhorst Blackhawk speaks of spending an hour in Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, of how she reclaimed her maiden name, of writing advice she finds most true, and so much more. Join us on Sunday, March 7, 2021 to hear Bohnhorst Blackhawk read with Jennine Capó Crucet, Koritha Mitchell, Keya Mitra, and Rhonda Welsh. Admission is free. Zoom login information will be shared prior to the event. Please RSVP here.

In this 2021 FPP interview with Dr. Terry Bohnhorst Blackhawk, Bohnhorst Blackhawk speaks of spending an hour in Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, of how she reclaimed her maiden name, of writing advice she finds most true, and so much more. Join us on Sunday, March 7, 2021 to hear Bohnhorst Blackhawk read with Jennine Capó Crucet, Koritha Mitchell, Keya Mitra, and Rhonda Welsh. Admission is free. Zoom login information will be shared prior to the event. Please RSVP here.

After decades of living and writing in Detroit, Michigan, you now live and write outside of New Haven, Connecticut. How has your new region and home impacted your writing, if at all?

It’s been a huge change for me and I don’t deny that it’s taken some getting used to. I am quite comfortable here, but leaving Detroit meant leaving a source of so much passion – many dear friends, fellow poets, my work with InsideOut, being a Kresge fellow and part of the incredibly vibrant cultural life of the city, the Detroit River, living and birding on the flyway, and memories of my beloved Neil Frankenhauser, the artist whose ashes we scattered in Toledo’s Maumee River in November 2019. It’s great to be close to family here, but I doubt I’ll ever have as passionate an attachment to a place as my connection to Detroit.

Before Covid, however, since being here gives easy access to New York City, I visited frequently. I also frequent Amherst MA from time to time, the site of Emily Dickinson’s family home and museum. I’ve made a number of ‘pilgrimages’ there to take part in programs, overnighting sometimes at the Amherst Inn, which is directly across the street from Her home. I wrote a recent poem, “In Her Chamber,” after spending an hour in Her bedroom, an experience one can purchase as a fundraiser for the museum. That poem is collected in my fifth full-length collection One Less River, which came out in 2019 from Mayapple Press. It’s the only New England poem in the collection; the first section is all poems about Detroit. I’ve been very lucky here to find some fine poetry friends, who have been lifelines, and I have a poem just out in Waking Up To The Earth: Connecticut Poets in a Time of Global Climate Crisis, a terrific anthology that along with the friendships makes me happy to be a Connecticut poet as well.

Please tell us about your current book-in-progress called “American Mercy.” Is there a founding story, or image, that guides you?

I’ve actually put that title to the side. I had thought about it as having to do with probing the nature of love, or its absence, at both a personal and a social justice level, with an emphasis on what Desiree Cooper has labeled “Writing While White,” but my current energies have been pulled more directly into poems about Neil, whom I still grieve tremendously. I have his paintings here in CT with me, and he is still very present in my heart, so I have been working and reworking a chapbook about him. The title is Maumee, Maumee, after what he called his “sacred” river where he would go day after day to sit and paint en plein air. Some poems from this collection were finalists for the Joy Harjo Prize from Cutthroat Magazine, and another received a Pushcart Prize nomination from Negative Capability, so I’m hopeful that the manuscript will find a publisher.

Many of us have long known you as Dr. Terry Blackhawk, but recently you’ve reclaimed your maiden name Bohnhorst. Would you share a bit as to why you’ve made this choice?

Well, here’s a fun fact: I didn’t marry into Blackhawk. In 1970, in Detroit, I married Evans Charley, a member of the Te-moak Band of Western Shoshone from Nevada. Our son Ned [Blackhawk], the Yale historian, is also an enrolled member. Ned Charley was an adorable six-year-old when his dad decided to change his name (and thus our family name) to something more reflective of his heritage. We divorced in 2005, but by then I had already established myself as a poet and nonprofit arts leader under the name Blackhawk. I got used to it, although when people wondered about its origin, I would sometimes say, “I’m the white lady with the Indian name.” A few months ago, however, when a member of my Unitarian congregation here in Connecticut approached me to ask how I “identify” (meaning which tribe), I realized that it was time to ward off any more confusion. I think the Bohnhorst Blackhawk combination is the best way to do that.

In 2016’s The Whisk and Whir of Wings we find a collection of some of your favorite bird poems written over the years. How do you experience the “whisk and whir” in your current living and writing?

I’d have to say the whisk & whir is mostly in memory now. That is, for the meantime at least, I guess I’m a rather lapsed birder. Not that Connecticut isn’t a fabulous place for birding. The shore of Long Island sound is especially wonderful. I’ve joined the CT Audubon and have explored some of the nature preserves, but I don’t have the energy for it that I once had. I am also the owner of a sweet little mixed poodle rescue dog, Max, who came into our family a few years ago and has become mine full time. Thanks to him, I walk a couple of miles every day, but walking a dog and birding do not go hand in hand.

Is there creative work by others that is inspiring you of late?

Over the last year or so, I’ve spent a lot of time writing blurbs for others. I think I’m going to call a halt to it, but it’s been great to get to know new collections by Judith Kerman, Derek Pollard, Jude Marr, and Mary Minock. And I can’t resist sharing my blurb for Pete Markus’s new and very moving collection, When Our Fathers Return to Us as Birds, coming out from Wayne State University Press in a couple of months. It’s great to bookend this FPP series with Mr. Pete – you’re lucky to have him! — and I know you’ll be as moved by the poems as I am. He wrote them as a record, to capture his daily process of grieving after his father died. He shared the poems with me privately before the press accepted them, and they were a real solace as I grieved Neil’s death. Others have also found that kind of comfort from the collection. So I don’t mind giving you a sneak peek at the blurb. Here it is. Walk the river with Peter Markus in his daily homage to his father. Take in the levees, the fish, the abandoned steel mill, the birds, the river air his father will no longer breathe—all rendered with steady wonder and “the clarity that death brings.” And take comfort. Rather than “let silence have its way with grief,” Markus gives us—in poems as translucent as the clearest river water—“no better way to say goodbye.”

After many years of teaching, and of leading and training other teachers and writers-in-the-classroom, you have given all kinds of instruction and advice for those wishing to develop their craft as poets and writers. Is there any advice that stands out to you now, that you think is most true?

I guess the main thing is for writers to get out of their own way, that is, to stay open to surprise and discovery and not get bogged down trying to make particular points. E. M. Forster’s “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” was a favorite classroom mantra of mine, and I often urged my students, when they would stare off into space as if searching for inspiration on the ceiling, by saying “Don’t think. Write!” I believe that writing itself overcomes the fear of writing. It generates new connections and unexpected ways of saying things. When a piece of writing feels safe or stale, I suspect that the writer is going over old ground and not, as Gertrude Stein would say, allowing “creation (to) take place between the pen and the paper, rather than beforehand in a thought.” I think that Peter Markus’s method of writing must follow or flow in this way, which might account for the purity and translucence of his work.

It is March 2021, the month we mark one year since the first cases of Covid-19 were known in this country. What about this past year has been most challenging for you? What has given you hope?

Keeping track of time has been the most challenging for me. In the summer I got together out of doors quite regularly with poet friends, which was a pleasure, but since the weather changed I haven’t gone out much, except to walk. One day blends into the next and the “before times” feel like a different life altogether. I’ve been able to stay in frequent touch with friends, though, which helps tremendously. And I’ve luckily been in a safe “bubble” with my son, new daughter-in-law and new grandson, and I see my older grandchildren regularly enough to make life very sweet indeed. The stupidity and venality of a huge section of the US electorate and their chosen “jefe” has, of course, filled me with dread, but the Biden administration’s resourcefulness and compassion do give me hope.

What does the future hold?

I kept a little apartment in Detroit, close to the Detroit River and the Eastern Market, so once the pandemic lifts I hope to be able to get back there at least a couple of times a year. I just completed my vaccinations, but I’m not in a big hurry to fly. I guess I’m still in a holding pattern, like the rest of us!