Join us virtually on Sunday, January 17th, 2021 for “The Way Forward,” a reading by the First Person Plural Reading Series featuring Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, Desiree C. Bailey, Roberto Carlos Garcia, Max S. Gordon, Sara Lippmann, Gloria Nixon-John, and Samantha So Lamb and Alex Torres who will read in memory of Anthony Veasna So. The reading is curated and hosted by Stacy Parker Le Melle. This is our fifth annual post-election reading, but instead of our focus being on “what just happened?” our readers will share work that speaks to what we must hold on to, what we must seek, what we must know and learn and feel as we find our way forward. The reading is from 6-8pm. Admission is free.

Please RSVP via Eventbrite here. You will be sent log-in instructions prior to the event.

About the readers:

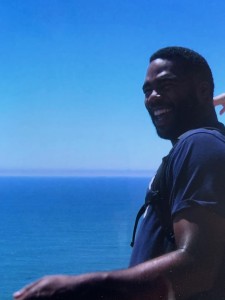

Ibrahim is a bright, playful spirit who authentically reflects and acts on bold questions. His artful blending of idealism and spiritual commitment with pragmatic application has led him into government, public administration, parenthood, and media. His unique voice has helped elevate the environmental vision of Islam, the spiritual opportunity of parenting, and the cultural and political side of sports and the ethical imperative when considering decisions about how we manage land, waters, and open space.

Ibrahim is a bright, playful spirit who authentically reflects and acts on bold questions. His artful blending of idealism and spiritual commitment with pragmatic application has led him into government, public administration, parenthood, and media. His unique voice has helped elevate the environmental vision of Islam, the spiritual opportunity of parenting, and the cultural and political side of sports and the ethical imperative when considering decisions about how we manage land, waters, and open space.

Ibrahim Abdul-Matin is an urban strategist whose work focuses on deepening democracy and improving public engagement. He has advised two mayors on the best ways to translate complex decisions related to the cost, impacts, and benefits of environmental policy on communities. He is the founder of Green Squash Consulting a management consulting firm based in New York that works with people, organizations, companies, coalitions and governments committed to equity and justice. He is the author of Green Deen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet and in addition to the New York Advisory Board of the Trust for Public Land he is sits on the board of the International Living Future Institute encouraging the creation of a regenerative built environment and Sapelo Square whose mission is to celebrate and analyze the experiences of Black Muslims in the United States.

Desiree C. Bailey is the author of What Noise Against the Cane (Yale University Press, 2021), selected by Carl Phillips as the winner of the 2020 Yale Series of Younger Poets. She is also the author of the fiction chapbook In Dirt or Saltwater (O’clock Press, 2016) and has short stories and poems published in Best American Poetry, Best New Poets, American Short Fiction, Callaloo, the Academy of American Poets and elsewhere. Desiree was born in Trinidad and Tobago, and grew up in Queens, NY.

Desiree C. Bailey is the author of What Noise Against the Cane (Yale University Press, 2021), selected by Carl Phillips as the winner of the 2020 Yale Series of Younger Poets. She is also the author of the fiction chapbook In Dirt or Saltwater (O’clock Press, 2016) and has short stories and poems published in Best American Poetry, Best New Poets, American Short Fiction, Callaloo, the Academy of American Poets and elsewhere. Desiree was born in Trinidad and Tobago, and grew up in Queens, NY.

Poet, storyteller, and essayist Roberto Carlos Garcia is a self-described “sancocho […] of provisions from the Harlem Renaissance, the Spanish Poets of 1929, the Black Arts Movement, the Nuyorican School, and the Modernists.” Garcia is rigorously interrogative of himself and the world around him, conveying “nakedness of emotion, intent, and experience,” and he writes extensively about the Afro-Latinx and Afro-diasporic experience. Roberto’s third collection, [Elegies], is published by Flower Song Press and his second poetry collection, black / Maybe: An Afro Lyric, is available from Willow Books. Roberto’s first collection, Melancolía, is available from Červená Barva Press.

Poet, storyteller, and essayist Roberto Carlos Garcia is a self-described “sancocho […] of provisions from the Harlem Renaissance, the Spanish Poets of 1929, the Black Arts Movement, the Nuyorican School, and the Modernists.” Garcia is rigorously interrogative of himself and the world around him, conveying “nakedness of emotion, intent, and experience,” and he writes extensively about the Afro-Latinx and Afro-diasporic experience. Roberto’s third collection, [Elegies], is published by Flower Song Press and his second poetry collection, black / Maybe: An Afro Lyric, is available from Willow Books. Roberto’s first collection, Melancolía, is available from Červená Barva Press.

His poems and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY Magazine, The BreakBeat Poets Vol 4: LatiNEXT, Bettering American Poetry Vol. 3, The Root, Those People, Rigorous, Academy of American Poets Poem-A-Day, Gawker, Barrelhouse, The Acentos Review, Lunch Ticket, and many others.

He is founder of the cooperative press Get Fresh Books Publishing, A NonProfit Corp.

A native New Yorker, Roberto holds an MFA in Poetry and Poetry in Translation from Drew University, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Max S. Gordon is a writer and activist. His work has also appeared on openDemocracy, Democratic Underground and Truthout, in Z Magazine, Gay Times, Sapience, and other progressive on-line and print magazines in the U.S. and internationally. His essays include “The Eroticism of Brutality – On Mary Trump’s ‘Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man’ and “How We’ll Get Over: Going to The Upper Room with Donald Trump.”

Max S. Gordon is a writer and activist. His work has also appeared on openDemocracy, Democratic Underground and Truthout, in Z Magazine, Gay Times, Sapience, and other progressive on-line and print magazines in the U.S. and internationally. His essays include “The Eroticism of Brutality – On Mary Trump’s ‘Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man’ and “How We’ll Get Over: Going to The Upper Room with Donald Trump.”

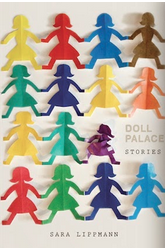

Sara Lippmann is the author of the story collections Doll Palace, long-listed for the 2015 Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and JERKS (forthcoming from Mason Jar Press.) She was awarded an artist’s fellowship in fiction from New York Foundation for the Arts, and her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Millions, Fourth Genre, Slice Magazine, Diagram, Epiphany and elsewhere. She’s landed on Wigleaf’s Top 50, and her stories have been anthologized in Mamas and Papas: On the Sublime and Heartbreaking Art of Parenting (San Diego City Works Press) and forthcoming in New Voices: Contemporary Voices Confronting the Holocaust (Blue Lyra Press) and Best Small Fictions 2020 (Sonder Press). Raised outside of Philadelphia, she lives and teaches in Brooklyn and co-hosts the Sunday Salon NYC.

Sara Lippmann is the author of the story collections Doll Palace, long-listed for the 2015 Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and JERKS (forthcoming from Mason Jar Press.) She was awarded an artist’s fellowship in fiction from New York Foundation for the Arts, and her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Millions, Fourth Genre, Slice Magazine, Diagram, Epiphany and elsewhere. She’s landed on Wigleaf’s Top 50, and her stories have been anthologized in Mamas and Papas: On the Sublime and Heartbreaking Art of Parenting (San Diego City Works Press) and forthcoming in New Voices: Contemporary Voices Confronting the Holocaust (Blue Lyra Press) and Best Small Fictions 2020 (Sonder Press). Raised outside of Philadelphia, she lives and teaches in Brooklyn and co-hosts the Sunday Salon NYC.

Gloria Nixon-John, Ph.D. Gloria’s novel The Killing Jar is based on the true story of one of the youngest Americans to have served on death row. Her memoir entitled Learning from Lady Chatterley is written in narrative verse and is set in Post WWII Detroit. Her chapbook, Breathe me a Sky, was recently published by The Moonstone Art Center of Philadelphia. She has published poetry, fiction, and essays in several literary journals and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize by A3 of London. Many of her essays and poems deal with her love of gardening, and with her love of, and care for, her horses.

Gloria Nixon-John, Ph.D. Gloria’s novel The Killing Jar is based on the true story of one of the youngest Americans to have served on death row. Her memoir entitled Learning from Lady Chatterley is written in narrative verse and is set in Post WWII Detroit. Her chapbook, Breathe me a Sky, was recently published by The Moonstone Art Center of Philadelphia. She has published poetry, fiction, and essays in several literary journals and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize by A3 of London. Many of her essays and poems deal with her love of gardening, and with her love of, and care for, her horses.

Gloria has collected an oral history of sculptor Marshall Fredericks for The Marshall Fredrick’s museum in Saginaw Michigan and has done oral history work for the Theodore Roethke House, also in Saginaw, Michigan. She currently works as an independent writing consultant for schools, libraries, and individual writers. Gloria lives in rural Oxford, Michigan with her horses, dogs, cats, husband Michael.

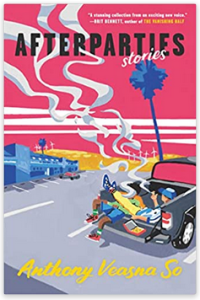

As Anthony Veasna So agreed to read for “The Way Forward” just days before he passed away in San Francisco, CA, I am grateful to be able to keep Anthony as part of the lineup in order to remember him and to honor his work. He will be memorialized by his sister Samantha So Lamb and his partner Alex Torres. – SPL

As Anthony Veasna So agreed to read for “The Way Forward” just days before he passed away in San Francisco, CA, I am grateful to be able to keep Anthony as part of the lineup in order to remember him and to honor his work. He will be memorialized by his sister Samantha So Lamb and his partner Alex Torres. – SPL

Anthony Veasna So (deceased) is a graduate of Stanford University and earned his MFA in Fiction at Syracuse University. His debut story collection, Afterparties, is forthcoming from Ecco/HarperCollins in August 2021, and his writing has been or will be published in The New Yorker, n+1, Granta, and ZYZZYVA. Born and raised in Stockton, CA, he lived in San Francisco, where he worked on an essay collection and a stoner novel of queer ideas about three Khmer American cousins—a pansexual rapper, a comedian philosopher, and a leftist illustrator.

Samantha So Lamb was born and raised in Stockton, California. Her parents are Cambodian refugees who escaped the Khmer Rouge. First in her family to graduate from college, Samantha decided to become a teacher. She dedicates her career to teaching elementary grades in urban neighborhoods and deeply believes in equitable access to rigorous education for all students, especially black and brown children. She currently lives and teaches in Richmond, California with her husband, her son, and dog.

Samantha So Lamb was born and raised in Stockton, California. Her parents are Cambodian refugees who escaped the Khmer Rouge. First in her family to graduate from college, Samantha decided to become a teacher. She dedicates her career to teaching elementary grades in urban neighborhoods and deeply believes in equitable access to rigorous education for all students, especially black and brown children. She currently lives and teaches in Richmond, California with her husband, her son, and dog.

Alex Torres has taught English in Bogotá, Colombia as a Fulbright Scholar, reported on venture capitalists & startups for Business Insider, and published academic research on nineteenth and twentieth-century US literary culture.

Curator and Host:

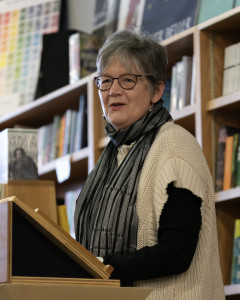

Stacy Parker Le Melle is the author of Government Girl: Young and Female in the White House (HarperCollins/Ecco), was the lead contributor to Voices from the Storm: The People of New Orleans on Hurricane Katrina and Its Aftermath (McSweeney’s), and chronicles stories for The Katrina Experience: An Oral History Project. She is a 2020 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow for Nonfiction Literature. Her recent narrative nonfiction has been published in Callaloo, Apogee Journal, The Atlas Review, Callaloo, Cura, Kweli Journal, Nat. Brut, The Nervous Breakdown, The Offing, Phoebe, Silk Road and The Florida Review where the essay was a finalist for the 2014 Editors’ Prize for nonfiction. Originally from Detroit, Le Melle lives in Harlem where she curates the First Person Plural Reading Series. Follow her on Twitter at @stacylemelle.

Stacy Parker Le Melle is the author of Government Girl: Young and Female in the White House (HarperCollins/Ecco), was the lead contributor to Voices from the Storm: The People of New Orleans on Hurricane Katrina and Its Aftermath (McSweeney’s), and chronicles stories for The Katrina Experience: An Oral History Project. She is a 2020 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow for Nonfiction Literature. Her recent narrative nonfiction has been published in Callaloo, Apogee Journal, The Atlas Review, Callaloo, Cura, Kweli Journal, Nat. Brut, The Nervous Breakdown, The Offing, Phoebe, Silk Road and The Florida Review where the essay was a finalist for the 2014 Editors’ Prize for nonfiction. Originally from Detroit, Le Melle lives in Harlem where she curates the First Person Plural Reading Series. Follow her on Twitter at @stacylemelle.

Allen Gee is the author of the essay collection, My Chinese America. He recently completed a novel, The Laborers, and is currently at work on At Little Monticello: the James Alan McPherson biography, (UGA Press). He’s been the Editor at Gulf Coast, Fiction Editor at Arts & Letters, and Editor of the multicultural imprint 2040 Books. His essay Old School won a Pushcart, and his work appears in numerous journals, as well as the anthology, Dear America. He is currently the D.L. Jordan Distinguished Chair of Creative Writing at Columbus State University where he also serves as the Director/Editor of CSU Press.

Allen Gee is the author of the essay collection, My Chinese America. He recently completed a novel, The Laborers, and is currently at work on At Little Monticello: the James Alan McPherson biography, (UGA Press). He’s been the Editor at Gulf Coast, Fiction Editor at Arts & Letters, and Editor of the multicultural imprint 2040 Books. His essay Old School won a Pushcart, and his work appears in numerous journals, as well as the anthology, Dear America. He is currently the D.L. Jordan Distinguished Chair of Creative Writing at Columbus State University where he also serves as the Director/Editor of CSU Press. New York Times-bestselling author Robert Jones, Jr., was born and raised in New York City. He received his BFA in creative writing with honors and MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Paris Review, Essence, OkayAfrica, The Feminist Wire, and The Grio. He is the creator of the social-justice social media community Son of Baldwin. The Prophets is his debut novel. Photo Credit: Alberto Vargas RainRiver Images.

New York Times-bestselling author Robert Jones, Jr., was born and raised in New York City. He received his BFA in creative writing with honors and MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Paris Review, Essence, OkayAfrica, The Feminist Wire, and The Grio. He is the creator of the social-justice social media community Son of Baldwin. The Prophets is his debut novel. Photo Credit: Alberto Vargas RainRiver Images. Kevin McIlvoy’s novel One Kind Favor (WTAW Press, May 2021) is his eighth published book. He has published five novels, A Waltz (Lynx House Press), The Fifth Station (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill; paperback, Collier/Macmillan), Little Peg (Atheneum/Macmillan; paperback, Harper Perennial), Hyssop (TriQuarterly Books; paperback, Avon), At the Gate of All Wonder (Tupelo Press); and a short story collection, The Complete History of New Mexico (Graywolf Press). His short fiction has appeared in Harper’s, Southern Review, Ploughshares, Missouri Review, and other literary magazines. His short-short stories and prose poems have appeared in The Scoundrel, The Collagist, Pif, Kenyon Review Online, The Cortland Review, Prime Number, r.k.v.r.y, Waxwing, and various online literary magazines. A collection of his prose poems and short-short stories, 57 Octaves Below Middle C, has been published by Four Way Books (October 2017). For twenty-seven years he was fiction editor and editor in chief of the national literary magazine, Puerto del Sol. He taught in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program in Creative Writing from 1987 to 2019; he taught as a Regents Professor of Creative Writing in the New Mexico State University MFA Program from 1981 to 2008. He has lived in Asheville, North Carolina since 2008.

Kevin McIlvoy’s novel One Kind Favor (WTAW Press, May 2021) is his eighth published book. He has published five novels, A Waltz (Lynx House Press), The Fifth Station (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill; paperback, Collier/Macmillan), Little Peg (Atheneum/Macmillan; paperback, Harper Perennial), Hyssop (TriQuarterly Books; paperback, Avon), At the Gate of All Wonder (Tupelo Press); and a short story collection, The Complete History of New Mexico (Graywolf Press). His short fiction has appeared in Harper’s, Southern Review, Ploughshares, Missouri Review, and other literary magazines. His short-short stories and prose poems have appeared in The Scoundrel, The Collagist, Pif, Kenyon Review Online, The Cortland Review, Prime Number, r.k.v.r.y, Waxwing, and various online literary magazines. A collection of his prose poems and short-short stories, 57 Octaves Below Middle C, has been published by Four Way Books (October 2017). For twenty-seven years he was fiction editor and editor in chief of the national literary magazine, Puerto del Sol. He taught in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program in Creative Writing from 1987 to 2019; he taught as a Regents Professor of Creative Writing in the New Mexico State University MFA Program from 1981 to 2008. He has lived in Asheville, North Carolina since 2008. of New York-CUNY. A graduate of Yale and Vanderbilt Universities, and a Professor of Spanish and Portuguese, her research interests focus on the cultural production of Black peoples throughout the Americas: the United States and Latin America, including Brazil, and the Caribbean. She is the editor of The Future Is Now: A New Look at African Diaspora Studies (2012) and Let Spirit Speak! Cultural Journeys through the African Diaspora (2012). She is the author of Oshun’s Daughters: The Search for Womanhood in the Americas (2014) and Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (2017). Her latest book, Racialized Visions: Haiti and the Hispanic Caribbean (2020) is an edited collection that re-centers Haiti in the disciplines of Caribbean, and more broadly, Latin American Studies.

of New York-CUNY. A graduate of Yale and Vanderbilt Universities, and a Professor of Spanish and Portuguese, her research interests focus on the cultural production of Black peoples throughout the Americas: the United States and Latin America, including Brazil, and the Caribbean. She is the editor of The Future Is Now: A New Look at African Diaspora Studies (2012) and Let Spirit Speak! Cultural Journeys through the African Diaspora (2012). She is the author of Oshun’s Daughters: The Search for Womanhood in the Americas (2014) and Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (2017). Her latest book, Racialized Visions: Haiti and the Hispanic Caribbean (2020) is an edited collection that re-centers Haiti in the disciplines of Caribbean, and more broadly, Latin American Studies.