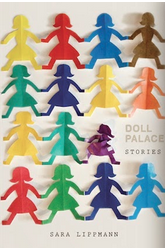

In this FPP Interview with fiction writer Sara Lippmann we learn how the “urgency and alienation and erasure” she felt as a new mother pushed her to create her short story collection Doll Palace, how people have given her “all kinds of shit” for her writing, how characters’ bad choices are often “what makes fiction compelling,” and so much more. Join us on Sunday, January 17th for “The Way Forward,” to hear Sara Lippmann read live, via Zoom, with writers Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, Desiree C. Bailey, Roberto Carlos Garcia, Max S. Gordon, Sara Lippmann, Gloria Nixon-John and Samantha So Lamb and Alex Torres who will be memorializing Anthony Veasna So. RSVP here. – SPL

In this FPP Interview with fiction writer Sara Lippmann we learn how the “urgency and alienation and erasure” she felt as a new mother pushed her to create her short story collection Doll Palace, how people have given her “all kinds of shit” for her writing, how characters’ bad choices are often “what makes fiction compelling,” and so much more. Join us on Sunday, January 17th for “The Way Forward,” to hear Sara Lippmann read live, via Zoom, with writers Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, Desiree C. Bailey, Roberto Carlos Garcia, Max S. Gordon, Sara Lippmann, Gloria Nixon-John and Samantha So Lamb and Alex Torres who will be memorializing Anthony Veasna So. RSVP here. – SPL

In your short story collection Doll Palace and in stories published since, you tell the stories of women and girls in such profound ways that readers experience the good, the bad, and the ugly of our lives. What first motivated you to tell your stories? Is that how you still feel today?

I’ve been obsessed with writing since high school but there is a difference between wanting to write and having something to say. So while a love of language might have first drawn me to the page, it’s taken longer to develop voice and to embrace impulses of story.

I’ve been obsessed with writing since high school but there is a difference between wanting to write and having something to say. So while a love of language might have first drawn me to the page, it’s taken longer to develop voice and to embrace impulses of story.

Doll Palace came out of an urgency and alienation and erasure I felt as a new mother. I remember strangers touching my belly when I was pregnant with my first kid — as if a woman’s body becomes public domain. Wield a stroller on the sidewalk and there’s no shortage of those who know better. And so the stories in some way are in direct conversation with that. My new collection, JERKS, is both a deepening and an extension of those themes. Characters feel trapped by their circumstances and their choices, by societal expectations and systems. But whereas Doll Palace is arguably grimmer and more static, JERKS features more quiet rebellions and uses dark humor and lots of lust and desire to chip away the confines that hold us back from our own selfhood, and freedom.

I was listening to an episode of the New Yorker fiction podcast this morning where Chang-rae Lee reads a Steven Millhauser story and in the conversation with Deborah Treisman that follows he says, “the genius of all great writers is they show us something about reality that disturbs and disorients” and although I would never in a million years put myself in the Millhauser stratosphere but I would say that what I’m trying to do is expose a reality that is often glossed over or brushed under the rug — and yes, it’s sometimes hard and sometimes tender and rarely pretty.

Do you ever encounter resistance to your topics or to your narrators? Or, do you ever find readers get uneasy with the truths of your stories?

I’ve gotten all kinds of shit for my writing. What does your husband think? Your family? Your children? It’s all enraging. My characters are not particularly “likable” — which, don’t get me started. Philip Roth once said, “Literature is not a moral beauty contest,” which is something I return to again and again. Not as an excuse or pass for irresponsible fiction. I have no patience for hateful characters, but I’m also not interested in characters who always take the moral high road. I am resistant to didactic or moralistic storytelling, unless it is somehow subverting a fableistic trope. My characters make bad choices. My characters let their jagged seams hang out and unravel. That, to me, is what makes fiction compelling. I’ve certainly been told my writing is crass and unsavory among other things which only makes me want to double down on that aspect of humanity. Not to provoke. Not for the sake of exhibitionism. But because I want to tell honest stories.

Has your storytelling changed over time? If so, how?

Over time, I’d say my work has become more honest. Yes, I’ve always written fiction. But the stories must ring true. Every sentence has to feel honest and true with a clear sense of imperative. Often this entails paring back on language I’ve gotten carried away with. The older I get, the less tolerant I’ve become of language for the sake of language. Nothing is precious. I’ve gotten a bit better at being less self conscious, at getting out of my own damn way. Sentences without a focused point of view are just words. If the writing is not in direct service to the story it gets cut.

As the First Person Plural Reading Series, we’ve always been interested in what it means to be “we” – with all of its promises, power, and problems. When do you feel most “we” and when do you feel most “I”? Does it matter?

I am a big sucker for a first person plural story. I often draft longhand so I try not to censor myself in whatever voice comes out and it’s sometimes slippery, like I’ll move from I to you to we in morning pages all the time. I’ve published a couple of stories using a collective we — which often slips in when talking about mothers and women and girls. I like to play with assumptions placed upon these groups and also to subvert them. To embody the collective and to challenge it, to bristle against its confines. Erasure happens when you are lumped into a category, so it’s important to locate the individual in the we. In JERKS, there is a story called Har-True that moves between first person plural and singular. I also think the collective lends itself well to flash (“Aromatherapy” and “Father’s Day” are two micro examples of that). There is so much to unpack. While there can be power in the plural there is also a danger of homogeneity. Two sides of a coin. One the one hand, a collective lends support and company. But there can also be peer pressure and mob mentality. Sometimes I watch both of these patterns play out on Twitter.

Is there a community (or a “we”) that is sustaining you now?

The writing community — both at large and immediate — sustains me. My students. Writing is lonely enough business, and it’s so easy to feel even more disconnected and disaffected right now when we can’t go anywhere, that I am incredibly grateful for writers I connect with online — and on the phone. And even on zoom, though I loathe it. I haven’t met with my own writing group in person for over a year but we started holding each other accountable to our own progress on longer projects and these daily check-ins and cheers are getting me through. I don’t know where I’d be without them.

Alexander Chee is the bestselling author of the novels The Queen of the Night and Edinburgh. He is a contributing editor at The New Republic, an editor at large at VQR, and a critic at large at The Los Angeles Times. His work has appeared in Best American Essays 2016, The New York Times Magazine, Slate, Guernica, and Tin House, among others. He is an associate professor of English at Dartmouth College. His first collection of essays, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2018.

Alexander Chee is the bestselling author of the novels The Queen of the Night and Edinburgh. He is a contributing editor at The New Republic, an editor at large at VQR, and a critic at large at The Los Angeles Times. His work has appeared in Best American Essays 2016, The New York Times Magazine, Slate, Guernica, and Tin House, among others. He is an associate professor of English at Dartmouth College. His first collection of essays, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2018.