FPP spoke with poet Carina del Valle Schorske via email about her grandmother’s railroad apartment, the coercive word known as “America”, her work on Puerto Rico En Mi Corazón, and so much more. Come to Silvana on Tuesday, December 5th, and hear Schorske read with Nicole Sealey, Victor LaValle, and Nandi Comer. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St., near Frederick Douglass Blvd, on the SW corner. Take the B/C to 116th and you’re there. 7pm.

FPP spoke with poet Carina del Valle Schorske via email about her grandmother’s railroad apartment, the coercive word known as “America”, her work on Puerto Rico En Mi Corazón, and so much more. Come to Silvana on Tuesday, December 5th, and hear Schorske read with Nicole Sealey, Victor LaValle, and Nandi Comer. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St., near Frederick Douglass Blvd, on the SW corner. Take the B/C to 116th and you’re there. 7pm.

Tell us about your Harlem. Harlem is in the corner of my eye. I can see it when I lean over the park with a cliff so sheer the grid couldn’t break its back. I walk back and forth across the park to bars and bookstores and the black archives of our extended Caribbean. To visit friends. I dance at the Shrine. My Columbia-subsidized studio drinks down its ration of blood.

My Harlem is Washington Heights and the railroad apartment where my grandmother has lived for more than sixty years at 156th and Broadway. The smell of her lobby is a wrinkle in time where I’m caught at the bottom of a pocket looking for the keys. I’m not invited to the parties that happened before I was born but I still spin the soundtrack.

My Harlem is Washington Heights and the railroad apartment where my grandmother has lived for more than sixty years at 156th and Broadway. The smell of her lobby is a wrinkle in time where I’m caught at the bottom of a pocket looking for the keys. I’m not invited to the parties that happened before I was born but I still spin the soundtrack.

My Harlem looks good in May when it’s wet and somehow I’m in love again. I’m late but he doesn’t mind. In my Harlem Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts is out with her pop-up shop selling rare magazines that shine like mirrors.

My Harlem looks good in May when it’s wet and somehow I’m in love again. I’m late but he doesn’t mind. In my Harlem Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts is out with her pop-up shop selling rare magazines that shine like mirrors.

Sometimes in my Harlem I hallucinate Helga Crane and we suck each other up like Quicksand. I’m quoting from that Harlem novel now: “She was, she knew, in a queer indefinite way, a disturbing factor.”

In addition to your own poetry, you’ve done significant translation work. Will you share your personal joys and challenges of translating other poets?

I recently made a statement on the topic! If the statement were a tweet, it would be: “How else is anything born but through a foreign body?” Translation troubles the capitalist logic of ownership that governs so many aspects of global culture. To whom does a translation belong? Translation’s trouble is its joy and its challenge. Sometimes it’s straight up legal trouble: ask any translator who’s struggled to secure the “rights” to bring a poet into a new language across centuries, embargos, repressions, family traumas, redrawn borders, battle lines, colonial bylaws, crypto-currencies.

When do you feel most “we” and most “I”?

Tfw someone else’s “I” resonates so strongly with my own that a “we” gets born and then I have to learn how to care for it. Isn’t that what reading is? Recently I’ve been returning to a (Puschart Prize nomianted!) poem by my friend Sheila Maldonado called “Temporary Statement,” which begins as a kind of cantankerous refusal of the statement or manifesto form–so often written in the first person plural. She writes her statement in the first person singular. Here I want to quote her almost in full:

“…I’ve forgotten how to break a line. The line breaks me. I use I too much. I do get

that the I on the page is still not me. I do get that. I don’t know if you get that. I don’t

know who I am in this time. I have lost a great love. I am suffering through a terrible

leader. I don’t know where to turn or who to be. I am looking for my days to recquire

some rhythm. I can’t be kind in the morning. I can’t be kind. I am mourning. I miss

touch. I miss conversations I had in the past. I miss the conversation I had with my past.

It is leaving me. I don’t mind erasing. I want to know who to address though.”

Calling on Sheila to speak for me in a voice of profound doubt about the possibility of connection (even with something called the self) reveals how much we need each other even when we’re aiming to speak for ourselves. What actions do I have to take to protect the space that allows her–or anyone–to be someone I want to be a “we” with? Very soon we’re back to basics: food, shelter, the right to work and leisure and care.

But I’m very much a believer in “begin where you are” and most of the time I think of myself as an individual, even if that’s a modern delusion. So I begin with my “I” as a kind of technology for cutting through my own bullshit. “I” as a slender blade like in that Neil Young song (he’s still going!): “the love I got for you is a razor love that cuts clean through.” Maybe to a we. Vamos a ver.

A poem of yours, a poem of someone else’s that you wish all of America could hear right now. Why?

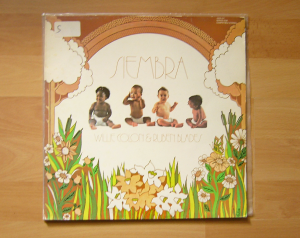

Honestly, I’m hung up on what “all of America” could possibly mean right now. Does that include Guantanamo? Guam? Everyone who’s crossed the border or is making plans to cross it right now? America Online? More pointedly for my own family, does that include Puerto Rico? Most of my cousins on the island would affirm the citizenship status of Puerto Ricans in a strategic bid for justice, especially in the wake of the hurricanes Irma & Maria. If we’re citizens, if we’re Americans, maybe FEMA will step up–that’s the logic. But if there’s a “we” that connects Puerto Rico and the mainland, El Salvador and California, Ismael Rivera and the Isley Brothers, I wouldn’t want to call it “America,” which has always seemed like a coercive word to me. It’s better in Latin America where they say it plural, Las Américas. I don’t know that there’s a single poem that can turn this imperial disaster into the right kind of “we.” But I’ve been listening to “Dime,” off of the classic Rubén Blades / Willie Colón salsa collab, Siembra, which came out in 1978. That’s New York, and one of the earliest album covers with babies on the cover way before Biggie:

The chorus asks, “Dime cómo me arranco del alma esta pena de amor” // “Tell me how I can pluck this pain of love from my soul.” But the song is so sweet, you want to stay in it. You don’t want to pluck it out. I guess for me the “America” question is, what would it mean to allow the pain of loving these plural places to form my soul? So my poem prescription is actually a song.

As for my own work, I’d probably direct you to an essay rather than a poem: an essay in which I ask how we bring migrant women–especially migrant women in Latin America–into the fold of U.S. literature as we translate them into English.

I realize now I’ve been answering your final question: “How has the natural and man-made disaster in Puerto Rico affected you and your work?” Answering it directly still feels too stark.

When Hurricane Maria hit, one of my cousins–we’ll call him my Tío José, because he’s that generation–was in the hospital. He was elderly and unwell. Last week, he passed away. The hurricane didn’t kill him but it certainly hastened his death. The last time I saw him was not this summer, but last, when he showed me the memoir he’d been writing for his daughter, and photographs of the farm where he was born. I want to honor the documentary impulse that sanctifies each bend in the river. That teaches me to trace its shape. When he showed me a map of the island he took my hand to point with his.

A solace these past few months has been the new connections with Puerto Ricans across the diaspora, especially Raquel Salas Rivera, who was already a friend, Erica Mena, and Ricardo Maldonado, who’ve let me help out as a translator and co-conspirator gathering and translating poems from contemporary Puerto Rican poets to print and sell as broadsides for hurricane relief. The project–Puerto Rico En Mi Corazón–will finally go live next week, just in time for the holiday season! Some of the poems included were written just days after Maria: that documentary impulse again. From the other side of a humanitarian flight off the island, Xavier Valcárcel writes, “Supongo que también las palomas tendrán que regresar al principio” // “I guess even the pigeons will have to go back to the beginning.”