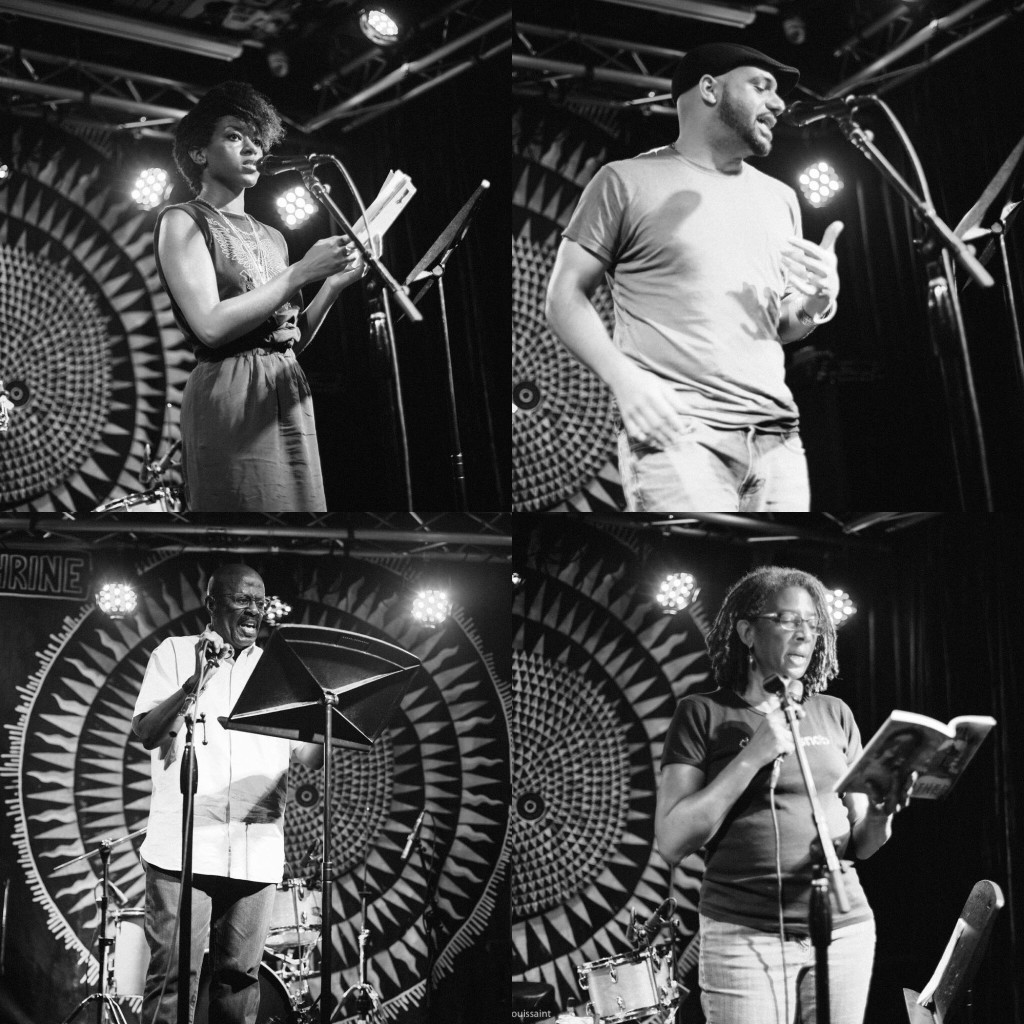

FPP spoke with Harlemite, community activist, and writer Charles Taylor about his love for Harlem, growing up in New York City, the killing of his teenage friend James Powell by police and resulting riots, the gentrification of Harlem, and whether locals and gentrifiers can, and should, work together to change gentrification’s course. See Taylor read on Tuesday, September 20th at the FPP Season Premiere at Shrine in Harlem, 7pm.

The title of your eBook-in-progress, Harlem 2 Harlem: Ghettopian Dreams, speaks of two Harlems. What are these two Harlems, and what do they each represent?

For me, the old Harlem represents a place where money was scarce and times were hard, but people came together to find ways to persevere. The Harlem of my youth provided my relatives and many of their neighbors with a life worth living. Of course theirs was poverty, crime and drugs—they were very much a part of the landscape.

Families of the present experience many of the same challenges faced by their counterparts from the past. There was always a socioeconomic divide in the Harlem community. There were the haves and have-nots. The modest-size middle class of my childhood enjoyed a plethora of advantages that made oppression more bearable. But the one thing that they had in common was their blackness—financial wherewithal notwithstanding, they were all still a part of the community and there was a level of begrudging acceptance that transcended class.

The new Harlem represents the ultimate in parallel universe living. As the middle class struggles to regain its economic footing, the poorest in our community suffer from the ravages of extreme poverty. We shouldn’t be fooled by stylish clothes, expensive sneakers and backpacks, and other external trappings valued by low income and working class residents. Many of them are working harder and longer for less and finding new ways to cutback to make ends meet. The real story is in the number of homeless people begging or living on our streets. There are tales to be told by the growing numbers of mentally ill people roaming aimlessly while engaged in lonely incomprehensible conversations. For this vulnerable population, it’s a live and let die existence.

Across the street, around the corner or sometimes next door, sits a gleaming new condo or a quaintly-appointed and refurbished brownstone occupied by newcomers to the community. These mostly white interlopers have grown in number like a chiapet over the last 20 years. Now, white Harlemites make up more than 10 percent of the population. Of course, there are a myriad of challenges when a group of comparatively affluent, culturally different people move into a minority community. There will always be things to work out such as noise levels—opposition to the noisy street life of Harlem as represented by the constant sounds of music and drumming across the blocks.

The most worrisome thing about the new Harlem is the stark and growing divide between the newly arrived residents and the longtime Harlemites. With gentrification comes a wave of amenities accompanied by cleaner streets, increased police presence, and lowered crime. Some of these benefits can be shared by all, but most of them are reserved exclusively for the privileged. Many people are worried about being pushed out of the community as more urban settlers lay claim to their homeland. I don’t know if that will ever happen. However, my wife and I have recently discussed the possibility of moving as a result of high rent and increased living expenses. We dread the idea, but must consider it as a real possibility. I can only imagine what it must feel like in a household with less income. At least we have options—we can probably find a more affordable place to live elsewhere in the city. If we’re lucky, we can find a way to generate more income and stay where we are. Most Harlemites don’t have these kinds of choices. The average income of a Harlem household is $37,000—barely enough to make ends met for a family with multiple children.

Of course, there is much to be said about the choices presented to various factions of the community—Whole Foods versus Food Town, upscale cafes and restaurants versus Popeye’s and McDonald’s. However, I believe that at the core of the quality of life is green power—what you can afford to buy or do.

In the new Harlem, newcomers hit the trains every weekday morning taking their kids to good schools on the Upper West Side, while most other local kids are stuck in low-performing Harlem schools. Some people have the luxury of living their lives straddling two worlds—home sweet Harlem for the comforts of daily life, and the rest of the city for everything else.

What strikes you most about the way the neighborhood has changed during your time here?

I appreciate many of the changes in Harlem over the years. I never imagined Harlem to be a place where I could enjoy cafes and some of the other upscale amenities. With few exceptions, I can’t buy the clothes I need in my community. I try to support the community by spending my money here—and I can do do that to a large degree. However, I find myself going downtown for many of the important items that I need.

I am concerned about the proliferation of taller buildings. I love the Harlem skyline and the unobstructed view of other parts of Manhattan. I am also bothered by what seems like the filling in of every available space. Now we have super thin buildings wedged between broad, beautiful structures. It’s an unsightly aberration of design.

One of the most unnerving changes is the disappearance of mom and pop shops. As comparative progress moves full steam ahead, the blazing bulldozers displace many of the shops that reliably served the community and offered tourists a taste of our culture. Rent gouging and exorbitant increases are to blame along with deals made with elected officials. On some level, streets and avenues are beginning to look like downtown locations. Along with the many churches and iconic buildings and landmark structures, mom and pop shops are at the core of the community—they are irreplaceable.

How can artists and writers respond to changes like the ones you describe, which can threaten the infrastructure and heart of communities of color?

Writers and artists can come together and engage all members of the community in understanding the vital needs of the community, and encourage them to make a difference. The sharing of artistic expression in all forms is one of the most potent ways to bring people together to share perceptions and opinions in a safe space to find common ground. Artists and writers have to find new opportunities for expressing their art and building a broader audience.

You’re the cofounder of Polarity, a Harlem-based social justice arts collective “focused on redirecting the trajectory of gentrification in communities of color.” What is your response to people who say that “gentrification is an inevitable force?” What work are you doing to redirect the trajectory of gentrification in Harlem?

In my opinion, gentrification is inevitable in that it’s here to stay. That doesn’t mean that the fight is over. We should identify flagrant abuses across the community and mobilize to shut them down or influence the outcome. For example, new housing without a reasonable number of truly affordable units should be vehemently opposed. The work that I’m doing is focused on the people who are living here now—all Harlemites. We seek to establish 1WorldTransition, a social change arts project that is designed to channel the trajectory of gentrification by challenging longtime residents and newcomers alike to collaboratively redirect the flow of sweeping community changes while building a more inclusive and equitable living environment. Through a mobile multimedia living-arts project, 1World will galvanize disparate community factions, examine the pros and cons of gentrification, and collectively determine strategies to reduce its harm and maximize its benefit. 1World will create a vibrant, interactive exhibit that will engage the community in confronting issues, finding common ground, and forging new alliances today for a better tomorrow.

What can gentrifiers do to be more aware of their impact on their new community? What changes would you like to see made to the way gentrifiers behave, shop, consume, and approach education—to name just a few factors—in their new community?

I understand that most of the newcomers can’t go to a hair salon or barbershop in Harlem. They may be hard-pressed to find clothing, furniture or other important items in local stores. However, they can commit to shopping locally whenever possible and attending local events, venues and activities to support cultural and business ventures. Most importantly, newcomers can ignite change in the miseducation of Harlem’s children. They can do this by enrolling their own children in our under-performing schools and then volunteering to make them better. Outspoken, educated parents can be influential in challenging the Department of Education while fundraising for increased school resources. This is a common occurrence at many schools citywide. It is a proven fact that all students benefit from a more diverse educational environment. A key component of creating a “good neighborhood” is the commitment residents have to educating their children. To sum it up, Harlem gentrifiers should start seeing Harlem as more than a convenient commute or an affordable living space—this can never be their home until they do.

Can and should locals and gentrifiers work together? If so, how?

Locals and gentrifiers can work together when gentrifiers decide to get their hands dirty and help address some of the ills that plague our community. Locals can acknowledge that they are short on answers to some of our most intractable challenges. The powers that be, local and city officials and major nonprofits, have not sufficiently met many of the community’s needs. It is time for the diverse residents of Harlem to come together to demand more from our elected officials while also taking matters into their own hands. We can’t be successful when significant swaths of our community are not engaged on either end of the socioeconomic continuum.

Can you tell me about your experiences growing up in, loving, and living in Harlem?

I’ve always loved Harlem. I drew my first breath at Sydenham Hospital on West 125th Street. Many of my mom’s relatives lived in various parts of Harlem. My paternal grandmother was my father’s only relative living up north. The hub of family activity was on 116th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues. My great-grandmother owned a small laundry on the block. I spent lots of time there while my parents were at work. We lived close by on 119th Street between 8th and Morningside Avenues in a tenement. My mom’s family was from Long Branch New Jersey by way of Mississppi, and my father was from a mere dot on a South Carolina map—Blackville.

My little sister and I spent so much time on 116th with my aunt, uncle, grandma and cousins and visiting relatives – it kind of felt like we lived there. At one point, we had five generations alive. However, it was not always a bed of roses. We had great family meals and loads of fun, but we also had a subliminal color code that dictated how much attention and privilege each of the children received.

We left Harlem for Staten Island when I was five. I briefly returned to Harlem as a 19-year-old hiding out with my 16-year-old runaway girlfriend. We shacked up in a quasi-abandoned building. This clandestine stint was short-lived.

During my young adult life and beyond, I lived all across the city and for a while, in the southern states reluctantly serving as a soldier. I still had relatives in Harlem, but the numbers slowly dwindled as the years passed. I set off on my big adventure and saw less and less of my Harlem relatives. As my aunts and uncles died, and their children married and moved away, we entered into a benign estrangement. There was no malice intended—on the contrary, we just went our separate ways.

I returned to Harlem years later in 1996. I came back to interview for a job at the Harlem YMCA—blocks from the Savoy Ballroom where my mother and father had danced their hearts out alongside legends like Red Foxx. This was the place where I had created wonderful childhood memories – memories that outshone actual events.

Initially, I was hired as the youth and family director. I was charged with revitalizing the Jackie Robinson Youth Center—once the gem of the illustrious Harlem YMCA. The center was closed for almost 4 years due to financial constraints. The Harlem Y board, and Congressman Charles Rangel, got together and raised over three-and-a-half-million dollars to revive the long-suffering youth refuge. We were off to the races.

After a long separation, I fell in love with Harlem all over again. I worked indefatigably for 12 hard years to build and grow quality programs for youth and families across the community. At the pinnacle of our work, we had programs at 12 off-sites and the main Harlem Y building. I managed more than 125 staff and influenced the lives of countless young people, parents and grandparents. We served more than 10,000 kids and families every year – a monumental, challenging and rewarding undertaking. I eventually oversaw youth and family programs, fund development, public affairs and communications, drug prevention education and a new Americans center. I left it all on the field at the Y.

As the years went by, I began finding new ways to influence the Harlem community and beyond. After being retrenched at the Y due to a downturn in the economy in 2008, I began utilizing the broad network of people that I had developed over the years. I tried my hand at politics for a while—supporting a campaign for city comptroller and another for congress. I worked with numerous local nonprofits and artists to secure funds and resources. I struck out on my own as a development consultant with mixed results. I soon learned that working for oneself is much harder than it seems.

In 2000, I met and married my third, and final wife. My wife, KD, is Japanese. She is a journalist who writes about American culture with an emphasis on black culture. She writes for Japanese print media and also coordinates film shoots. KD also conducts tours of East Harlem, West Harlem, Central Harlem, Washington Heights, and the South Bronx. KD came to America as a young woman, learned the language and mastered her craft. She inspired me to be a better man. We adopted a fantastic son, Fernando, now 12 years old, and decided to stay in Harlem. Harlem is now an integral part of our lives – the good, the bad, and the ugly.

What past experiences have influenced and informed your work?

Several key childhood experiences helped me develop the kind of empathy and understanding I would draw on in later life. As a child, I was acutely aware how my dark skin impacted all those around me. My lighter skinned adult relatives always talked about my “keen features” and thin lips—another way of saying I was dark with redeeming qualities.

As a small boy living in a strange land, Staten Island, I quickly learned what some white kids saw when they looked at me—something distasteful—something their parents didn’t like. In my first Staten Island home, the Stapleton Houses, one of two little Italian boys about my age hit me in the chin with a well-aimed tomato soup can top. I took my tear-soaked, bloody face upstairs seeking solace. My mom was horrified. My father snatched me by the collar and dragged me down three flights of stairs. He threw me at the boys and told me to fight. I closed my eyes and swung wildly at the boys. He then went and spent money he couldn’t spare to buy a set of boxing gloves. He made arrangements to teach me and the only other black boy in school how to box. My father was a shipping clerk in a coat factory. He was also a very tough former amateur boxer—an unhappy man who only took crap at work. In his real life, he was like a quiet storm. Everyone knew not to mess with Charlie—a nice guy, but a fierce adversary.

When my father thought I was ready, he exhorted me to walk up to a group of white kids on our block and randomly punch one in the face. I received a royal beatdown for my trouble. I accosted the group again and again, until one day, they saw me coming and ran. For the first time, I was filled with confidence. I didn’t have to fight—the bullies went looking for someone who wouldn’t fight back. Most of my former tormentors stayed away from me, but others befriended me.

My beautiful Staten Island housing project, Markham Gardens—stoop, front yard and back yard, like a real home. It was a heavenly place to live. Unfortunately, no one would play with me. The kids in the complex were instructed by their parents to stay away from me—I was the only black kid around. It took almost a year to find my first friend, Richie Riposo, a bushy-haired Italian classmate. We would wave at one another, but could only talk in school. One day, after many tries, Richie succeeded in defying his mom’s order to stay away from me. That was all I needed—the boycott was over. Richie and I played in my yard every day after homework. Soon, other kids joined us and I had a new treasure – a social life. I was just becoming popular when we moved to the Bronx.

I was 10 when we moved to the Soundview Houses in Bronx. It was a racially and ethnically mixed project with equal numbers of black, white and Latino residents. For the most part, the kids in our complex got along pretty well. The community outside the project property consisted of white homeowners who resented our presence. We all shared a fragile peace in a polarized community. Despite the tension, and occasional incident, the road to adolescence was filed with wonderful adventures and extraordinary friendships. Jimmy Powell was one of those special friends.

Jimmy lived in the building behind mine. I used to visit his house often. His mom, Mrs. Powell was a doting parent who treated every child with great care. He was a wise-cracking little guy—skinny with a lot of bravado. I taught Jimmy to box, and he tried to teach me to skate. He was part of my crew. We all had one thing in common—a commitment to squeeze every drop of fun out of each day.

While going to summer school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Jimmy got into an altercation with the super of a building. The mostly black and Latino summer school students were from outside of the ritzy neighborhood in the ’70s. The residents resented having the noisy teens sitting on their stoops and horsing around on their blocks during lunch breaks.

Jimmy and the super exchanged words—the N-word was uttered and the unexpected happened. The super sprayed Jimmy with a water hose and all hell broke loose. Jimmy and some of his friends chased the super into his building, but they couldn’t catch him. An off-duty detective was leaving a TV repair shop on the corner. He saw the tail end of the incident, and began chasing Jimmy and his friends. Two of the cop’s three shots hit and killed Jimmy in front of his classmates and local residents.

Jimmy’s death set off six nights of rioting across Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. More than 4,000 people were involved in the riots which devastated the black community. Hundreds of people were injured and many more were arrested—one person died. It is believed that the Harlem riot ignited other riots in July and August in cities including Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Rochester, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Jersey City, New Jersey; and Elizabeth, New Jersey. I experienced the harlem riot with a group of friends. It was the scariest thing I’d ever seen.

It was hard to reconcile so much devastation being connected to the life of James Powell —my skinny little teen friend who should have readily survived the incident that wantonly took his life. Controversy swirled around the incident. The cop claimed that Jimmy had lunged at him with a knife. Par for the course, the officer was cleared of any wrongdoing by a grand jury, and charges were dropped.

The aftermath of the riot yielded some good things for the Harlem community. An experimental anti-poverty program, Project Uplift, provided thousands of jobs to young Harlemites. This reactionary triage was tantamount to putting a bandaid on a bullet wound, however, it calmed things down for a while. Unfortunately, Jimmy wasn’t around to get one of those jobs.

In my Bronx elementary school, a fifth grade teacher asked my mom why I insisted upon coloring every character that I drew brown. My mom, an accomplished artist, said that she had encouraged me to draw whatever I felt. The teacher said that she understood, but she seemed very uncomfortable with the idea. She had the temerity to suggest to my mom that people came in all colors. I never got an A in that teacher’s class again, even though I could draw better than most of the other students. I didn’t care – I kept making my characters brown. The teacher stopped asking me to share my work with the class.

These childhood experiences taught me volumes about how and why people accept or reject one another—the essence of all relationships. It exposed me to unbridled hatred, unrelenting loneliness, unconditional love, unbreakable friendship, and the power of one person to overcome obstacles and make good things happen.

What is your vision for the future of Harlem?

My vision of the future of Harlem is a community that maintains its cultural identity while embracing newcomers without hesitating to challenge them to become full and active members of the community. I see a community where the focus is on the quality of life for all its members—from the most affluent residing in opulent mini-enclaves to the middle class fighting back against burgeoning rents and reduced services to those scrambling in pockets of poverty, looking for any way out.

The challenges faced by black and brown Harlemites and other people of color in similar communities lead to the same conclusion: We’re stuck between a liberal and a GOP place. We need new ears and hands that will listen to our issues and work with us to make real change.

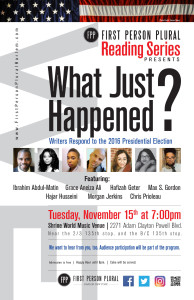

On Tuesday, November 15th, FPP will focus on the 2016 presidential election. As in: what just happened? We have a fantastic lineup of writers to help us make sense of – or complicate further – what has been a wild and wrenching year: Ibrahim Abdul-Matin; Grace Aneiza Ali; Hafizah Geter; Max S. Gordon; Hajar Husseini; Morgan Jerkins; and Chris Prioleau. We want to hear from you, too. Audience participation will be part of this program.

On Tuesday, November 15th, FPP will focus on the 2016 presidential election. As in: what just happened? We have a fantastic lineup of writers to help us make sense of – or complicate further – what has been a wild and wrenching year: Ibrahim Abdul-Matin; Grace Aneiza Ali; Hafizah Geter; Max S. Gordon; Hajar Husseini; Morgan Jerkins; and Chris Prioleau. We want to hear from you, too. Audience participation will be part of this program. Ibrahim Abdul-Matin is the author of Green Deen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet and contributor to All-American: 45 American Men On Being Muslim. He is a former sustainability policy advisor to New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and founder of the Brooklyn Academy for Science and the Environment. In 2013, Ibrahim was honored by NBC’s TheGrio.com as one of 100 African Americans Making history today. He currently serves as the Director of Community Affairs at the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. He has experience in the civic, public, and private sectors, and with government, public administration, and media. Ibrahim earned a BA in History and Political Science from University of Rhode Island and a master’s in public administration from Baruch College, City University of New York.

Ibrahim Abdul-Matin is the author of Green Deen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet and contributor to All-American: 45 American Men On Being Muslim. He is a former sustainability policy advisor to New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and founder of the Brooklyn Academy for Science and the Environment. In 2013, Ibrahim was honored by NBC’s TheGrio.com as one of 100 African Americans Making history today. He currently serves as the Director of Community Affairs at the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. He has experience in the civic, public, and private sectors, and with government, public administration, and media. Ibrahim earned a BA in History and Political Science from University of Rhode Island and a master’s in public administration from Baruch College, City University of New York. Grace Aneiza Ali is an independent curator, faculty member in the Department of Art & Public Policy, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University and Editorial Director of OF NOTE — an award-winning online magazine on art and activism. She has served as Editor & Digital Curator for several of the magazine’s art and social justice issues, including: The Water Issue, The Burqa Issue, The Imprisoned Issue, and The Immigrant Issue. Her essays on photography have been published in Harvard’s Transition Magazine, Nueva Luz Journal, Small Axe Journal, among others. In 2014, she received the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Curatorial Fellowship. In 2016, she served as curator for Un|Fixed Homeland at Aljira, a Center of Contemporary Art, an exhibition which brought together global Guyanese artists using photography to explore issues of migration and diaspora. Highlights of her curatorial work include Guest Curator for the 2014 Addis Ababa Foto Fest; Guest Curator of the Fall 2013 Nueva Luz Photographic Journal; and Co-Curator/Host of the Visually Speaking photojournalism public program series at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center. Ali is a World Economic Forum ‘Global Shaper’ and Fulbright Scholar. She holds an M.A. in Africana Studies from New York University and a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Maryland, College Park, where she graduated magna cum laude. Ali was born in Guyana and lives in New York City.

Grace Aneiza Ali is an independent curator, faculty member in the Department of Art & Public Policy, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University and Editorial Director of OF NOTE — an award-winning online magazine on art and activism. She has served as Editor & Digital Curator for several of the magazine’s art and social justice issues, including: The Water Issue, The Burqa Issue, The Imprisoned Issue, and The Immigrant Issue. Her essays on photography have been published in Harvard’s Transition Magazine, Nueva Luz Journal, Small Axe Journal, among others. In 2014, she received the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Curatorial Fellowship. In 2016, she served as curator for Un|Fixed Homeland at Aljira, a Center of Contemporary Art, an exhibition which brought together global Guyanese artists using photography to explore issues of migration and diaspora. Highlights of her curatorial work include Guest Curator for the 2014 Addis Ababa Foto Fest; Guest Curator of the Fall 2013 Nueva Luz Photographic Journal; and Co-Curator/Host of the Visually Speaking photojournalism public program series at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center. Ali is a World Economic Forum ‘Global Shaper’ and Fulbright Scholar. She holds an M.A. in Africana Studies from New York University and a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Maryland, College Park, where she graduated magna cum laude. Ali was born in Guyana and lives in New York City. Hafizah Geter is a 2014 Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship finalist. Her poems have appeared in RHINO, Drunken Boat, Boston Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, and Narrative Magazine, among others. She is on the board of VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts, a poetry editor for Phantom Books and co-curates the reading series EMPIRE with Ryann Stevenson.

Hafizah Geter is a 2014 Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship finalist. Her poems have appeared in RHINO, Drunken Boat, Boston Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, and Narrative Magazine, among others. She is on the board of VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts, a poetry editor for Phantom Books and co-curates the reading series EMPIRE with Ryann Stevenson. Max S. Gordon is a writer and performer. He has been published in the anthologies Inside Separate Worlds: Life Stories of Young Blacks, Jews and Latinos (University of Michigan Press, 1991), and Go the Way Your Blood Beats: An Anthology of African-American Lesbian and Gay Fiction (Henry Holt, 1996). His work has also appeared at The New Civil Rights Movement, openDemocracy, Democratic Underground and Truthout, in Z Magazine, Gay Times, Sapience, and other progressive on-line and print magazines in the U.S. and internationally. His recent published essays include, “Bill Cosby, Himself: Fame, Narcissism and Sexual Violence”; “The Cult of Whiteness: On Donald Trump, #OscarsSoWhite and the end of America” and “Be Glad That You are Free: On Nina, Miles Ahead, Lemonade, Lauryn Hill and Prince”.

Max S. Gordon is a writer and performer. He has been published in the anthologies Inside Separate Worlds: Life Stories of Young Blacks, Jews and Latinos (University of Michigan Press, 1991), and Go the Way Your Blood Beats: An Anthology of African-American Lesbian and Gay Fiction (Henry Holt, 1996). His work has also appeared at The New Civil Rights Movement, openDemocracy, Democratic Underground and Truthout, in Z Magazine, Gay Times, Sapience, and other progressive on-line and print magazines in the U.S. and internationally. His recent published essays include, “Bill Cosby, Himself: Fame, Narcissism and Sexual Violence”; “The Cult of Whiteness: On Donald Trump, #OscarsSoWhite and the end of America” and “Be Glad That You are Free: On Nina, Miles Ahead, Lemonade, Lauryn Hill and Prince”. Hajar Husseini was born in 1991 in Iran to an Afghan immigrant family. After the collapse of the Taliban regime, her family came back to Afghanistan when she was thirteen. After graduation from high school, she worked for several non-profit organizations. She started writing for Afghan Women Writing Project in April 2015. Her involvement with AWWP lead her to collaborate on a song about domestic violence with Eleanor Dubinsky. Currently based in Troy, NY, she attends The Sage Colleges where she received a full undergraduate scholarship from the Initiative to Educate Afghan Women to study “Writing and Contemporary Thought.” She wants to become a writer, a journalist, and a literary translator.

Hajar Husseini was born in 1991 in Iran to an Afghan immigrant family. After the collapse of the Taliban regime, her family came back to Afghanistan when she was thirteen. After graduation from high school, she worked for several non-profit organizations. She started writing for Afghan Women Writing Project in April 2015. Her involvement with AWWP lead her to collaborate on a song about domestic violence with Eleanor Dubinsky. Currently based in Troy, NY, she attends The Sage Colleges where she received a full undergraduate scholarship from the Initiative to Educate Afghan Women to study “Writing and Contemporary Thought.” She wants to become a writer, a journalist, and a literary translator. Morgan Jerkins is a writer living in Harlem. Besides being a Contributing Editor at Catapult, her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, ELLE, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, and BuzzFeed, among many others. Her debut essay collection, This Will Be My Undoing, is forthcoming from Harper Perennial. She received her Bachelor’s in Comparative Literature from Princeton University and MFA in Writing and Literature from Bennington College.

Morgan Jerkins is a writer living in Harlem. Besides being a Contributing Editor at Catapult, her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, ELLE, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, and BuzzFeed, among many others. Her debut essay collection, This Will Be My Undoing, is forthcoming from Harper Perennial. She received her Bachelor’s in Comparative Literature from Princeton University and MFA in Writing and Literature from Bennington College.