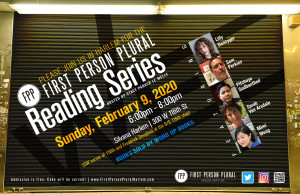

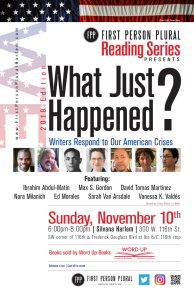

“The courageousness of the readers who come to read for us has goaded me into being less afraid,” says poet Sam Perkins when considering the impact of co-curating Bloom Reading Series in Washington Heights. In this FPP Interview, Perkins describes translation work as “watchmaking with words,” meditates on Cynthia Cruz’s “melancholia of class,” shares guidance for emerging writers and so much more. Read his words then hear Perkins read live with Lilly Dancyger, Pitchaya Sudbanthad, Sarah Van Arsdale, and Mimi Wong this Sunday at Silvana from 6-8pm. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Books sold by Word Up! Books. Admission is free. Please RSVP via Eventbrite here. – SPL

“The courageousness of the readers who come to read for us has goaded me into being less afraid,” says poet Sam Perkins when considering the impact of co-curating Bloom Reading Series in Washington Heights. In this FPP Interview, Perkins describes translation work as “watchmaking with words,” meditates on Cynthia Cruz’s “melancholia of class,” shares guidance for emerging writers and so much more. Read his words then hear Perkins read live with Lilly Dancyger, Pitchaya Sudbanthad, Sarah Van Arsdale, and Mimi Wong this Sunday at Silvana from 6-8pm. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Books sold by Word Up! Books. Admission is free. Please RSVP via Eventbrite here. – SPL

In Thirteen Leaves: Selected Poems of Contemporary Chinese Poets, we read your translation work with Joan Xie. Tell us what drew you to translation and these poets in particular. What did you learn from your partnership and this work?

Joan Xie is a remarkable writer and poet I met through Cornelius Eady’s class at the 92nd Street Y a few years ago. Though English isn’t her first language, Joan wields it fearlessly. She knows the contemporary literary scene in China very well, travels there regularly, and reads widely–both the approved writers as well as those who are persecuted or in exile. She collected and translated into English about 100 poems from 13 writers all over China, not just big city intelligencia but those from regional cities in the center and west of the country. I worked on them after that, going into the etymology and alternate meanings of the Chinese characters and suggesting alternative renderings in English. It is like watchmaking with words. It took over a year of word-wrestling with Joan. We’re working on an expanded version now.

Tell us about your current writing work. What inspires you of late?

My main goal as a writer in recent years is to be less careful, less craft-obsessed. I co-curate a reading series here in New York (and draw huge inspiration from FPP), and when I hear younger poets read, they have such enviable swing. They use a big brush on a big canvas and go corner to corner. Too often I’ll labor over a line or

My main goal as a writer in recent years is to be less careful, less craft-obsessed. I co-curate a reading series here in New York (and draw huge inspiration from FPP), and when I hear younger poets read, they have such enviable swing. They use a big brush on a big canvas and go corner to corner. Too often I’ll labor over a line or  a stanza when I should have either dropped the poem or shoved it out the door. One poet who does that really well is Cynthia Manick, but there are so many. I just heard Rosebud Ben-Oni read at Astoria Bookstore and I thought: Mae West meets Sylvia Plath, brassy,

a stanza when I should have either dropped the poem or shoved it out the door. One poet who does that really well is Cynthia Manick, but there are so many. I just heard Rosebud Ben-Oni read at Astoria Bookstore and I thought: Mae West meets Sylvia Plath, brassy,

Someone who’s had a big influence in the last year or so is Cynthia Cruz. Her poetry and essays explore what she calls the Melancholia of Class. She defines it in a special way — that I interpret in my own way as the pain of losing of past identities, your relationship with your family changes in ways that it can feel like a loss, the memories of home, friends, and all that filtered through your adult sense of class and position in society, the degree to which you had and have agency over you life. Are you free or just buffeted by forces beyond your control. The political dimensions of this are, of course, enormous. Call it melancholic class consciousness. Marx filtered though Marguerite Duras with illustrations by Käthe Kollwitz and Art Spiegelman.

That’s a long winded way of saying that my writing is gaining lots of energy from my grappling with the forces that made me, my delusions and hopes, my assumptions, and fears. Values that were chimeras; moments when I gave people the keys and said, “you drive” when I was the one who knew where I should go but zipped it up. So all that new wider consciousness of the different classes I occupy as a white man of a certain cultural class, financial class, social class, overlaid onto my uniquely fertilized psychological seed bed … makes for fruitful writing.

As co-curator of Bloom Reading Series, you’re a dedicated and loyal literary arts community builder. What has this work taught you, especially about your own work?

I have kind of a roundabout answer. Sarah Van Arsdale and I look for writers who are dedicated to the exploration of themselves and their world, our world. Writers who have a take that’s unique to them. Rough around the edges, unpolished in some areas — that’s okay, as long as you can see that they’re in it for the long haul, and that they’re committed to getting better at their craft. Poetry in particular, and creative writing generally, can make shy people bold and can help others become bold about their lives. Our audience is made up of people who self-select for being curious about lives not their own. They want to be taken places, shown new things, and shown old things in a new way. To run a reading series with any kind of sincerity is an exercise in helping people see the world as it is really experienced by others. It is as close as you get to holding hands with and looking into the eyes of strangers as they tell you about themselves. I think if politicians went to a reading once a month the world would be a better place.

The courageousness of the readers who come to read for us has goaded me into being less afraid, to take more risks, write longer, write more — even if it’s “worse,” — and to throw away more. Be less worried about shame and ridicule and being judged.

It’s 2020. What gives you hope? What gives you pause?

I’m not a “political” person and I have NO CHOICE but to be a political person. I was talking to Sarah Van Arsdale about this the other day:

Frustrated to tears that nothing we do politically seems to work to stop the sociopath in the White House; seeing that no norms hold him, that no amount of facts or truth has any effect on his party, etc etc., it looks to me like the progressive side is lashing out at their own over the pettiest things. We’ve been so bullied and frustrated by the political class, by the hammer lock of money, by the self-dealing cronyism, by the hovering anxiety of losing our jobs, our healthcare, our homes, that we’re turning on each other. I am in awe of your resilience and belief in social and political engagement. Listen to Leonard Cohen song “Everybody Knows” to get a sense of what I’m feeling.

When do you feel most “we”? When do you feel most “I”?

An answer by way of a story. On the recommendation of a friend who teaches at Yale, Sarah and I invited a young short story writer to come read. Mae Mattia was transitioning and now “she;” she had just graduated and was starting an MFA at Hunter. She was beautiful, proud, bashful, a little gawky, just getting steady in this new life. She came to read a short story at Bloom. I was so happy, I can’t describe it. Here we were catching this person just as she was taxiing down the runway, just taking off, and we were putting air under her wings. But what really swelled my heart was she brought her girlfriend, her mom and dad, and her little sister. They ALL came to hear her read at Bloom as a family. I felt like “I” am — a straight guy with grown sons. I also felt like I was the social director for the coming millennium who’d been given this gift that allowed me and everyone there to feel that we were “we.”

Tell us about your Harlem.

Food and music — what else is there? Silvana, The Shrine, Yatenga Cafe, Harlem Shambles Butchers, and of course, the mind-and-heart-food you create at FPP.

Who are writers that we should be reading right now?

Right now I’m reading writers who combine forms — or at least compression — with emotion. In addition to those already mentioned I’d say Louise Glück, Larry Levis, Nathan McClain, Elaine Equi, Bill Knott, Patricia Smith, and Maya Phillips (Erou), C.K. Williams, Philip Larkin. And here’s one for today: Alexander Pope. Try the Dunciad to get a taste of what a cloacal mess we’re in today. He was brilliant. Also William Blake, a poet I admire more than love, Keats and Wordsworth. For the current age: George Orwell and Joan Didion, but you knew that.

What advice would you give emerging writers today?

Avoid destructive emotional attachments. Get used to being alone. Cultivate it. Find a way to stop doubting yourself. Get plenty of sleep and exercise. Say less, save it for the page. Do the dishes, make the bed. Mind the pennies. Beware of social media. Read something good every day. Write every day. Go to literary readings like First Person Plural and Bloom Readings and Soul Sister Revue. If you can’t do any of that, um … marry rich.

If you could whisper something to us as we sleep tonight, what would it be?

“You are better than you fear

in ways you don’t yet understand.

Don’t quit.”