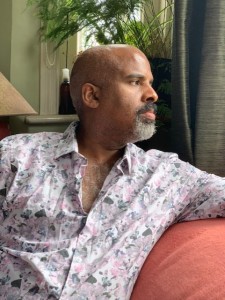

In this 2019 FPP Interview with Max S. Gordon, he shares with us his conviction that only poetry can fight vulgarity, that real poetry “makes sure that evil doesn’t have the last word.” Hear Gordon read live tonight at “What Just Happened: Writers Respond to Our American Crises” at 6pm this Sunday, November 10th at Silvana in Harlem. He’ll be joined by Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, David Tomas Martinez, Nara Milanich, Ed Morales and Sarah Van Arsdale. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Admission is free.

In your recent essay on Ava DuVernay’s four-part Netflix series on the Exonerated Five, When They See Us, you describe what you call “12 Years a Slave Syndrome,” or the refusal of some of us to watch movies that we fear will be more traumatizing than redemptive. You make a strong and beautiful case for watching When They See Us. What still stays with you?

What gives me hope is that despite all that is wrong, there is still a lot of creativity. We are hearing more from voices we haven’t heard from before. And truths are being told, lies uncovered. I felt this way when I watched the series, When They See us.

I believe that part of what has been so difficult over the last four years is that we, as a country, under the leadership of this man, have moved deeper into vulgarity. It isn’t like we weren’t warned. The comments about Mexicans being rapists, The Obama/Birther “movement”, and “Grab ‘Em By The”…, are all individually obscene – each comment mortifying on its own. Any of those transgressions should have had the power, if we were listening, to stop us in our tracks.

But like checkpoints, once you pass one, you find yourself further in the new country, until you reach the next checkpoint. We have allowed so much vulgarity to go unchecked that now we are no longer bystanders, we have lost the right as a country to be appalled by this man. Any attempts to say, “Oh my, I can’t believe he said that” are disingenuous, and the rest of the world judges us. We are approaching the point where no one will believe that this was only a grand error of judgment, an offending sensibility, an aberration, a country hijacked by a monster. We are the monsters. The more we enable him, the more he continues to defines us. We say we’ll leave, that one day we’ll “put our foot down,” but we all know people who say, “If he cheats one more time, I’m leaving” and we just nod and pour them another cup of coffee, because we know they aren’t going anywhere. Condemning Trump at this point, expressing outrage without action, is just a bunch of words, “breaking news” on CNN. If what we’ve seen at this point isn’t enough to let us know, then something is deeply wrong, not with him, but with us.

The answer to vulgarity – as I plan to speak about at our event – is not more vulgarity, it is poetry. When asked about writing the novel Beloved, author Toni Morrison said in an interview:

“There is so much more to remember and to describe for purposes of exorcism…things must be made, some fixing ceremony, some memorial, something, some altar, somewhere, where these things can be released, thought, and felt…The consequences of slavery only artists can deal with. There are certain things that only artists can deal with. And it’s our job.”

In When They See Us, Ava DuVernay did her job; she took a profound cultural obscenity, the incarceration of the innocent, and children scapegoated because of their race, and showed us, particularly in the episode devoted to Korey Wise and that stunning performance by Jharell Jerome, the triumph of the human spirit. What happened was so ugly and unfair and such an indictment of us as Americans and of American racism, some people don’t want to talk about it, don’t want to look. Just to read the court documents, to follow the story in its rawest form, can feel sometimes as if it will overwhelm us. But what an artist can do is make something beautiful, and there is a lot of beauty in When They See Us. Which isn’t to say that anything is being covered up or denied; real poetry brings us closer to the truth, not further away from it.

We seem to have a man in office who has no use for art, for poetry, for creativity. We never hear this man quote from his favorite poets, we never hear which political leaders have inspired him, we don’t know what music he likes, or if he listens to Bach, or Liszt, or Joni Mitchell or Iron Maiden. Maybe he’s been sharing this somewhere and I’ve missed it, but I feel I’ve been watching him pretty closely and I have no idea what inspires him other than money and power and ass. I even suspect he refuses to have a dog because his narcissism is so profound he doesn’t want to even compete with a puppy for attention. Poetry is like holy water at an exorcism for this president. He may have no use for it, but it is the only way back for the rest of us, it is the only thing that can restore us, wake us up from the dream.

I wrote about When They See Us because I think it is a story of redemption, not for the Exonerated Five, but for us as a society. We need to be reminded by our artists that there is always a path, if we are honest about who we are and what we’ve done. Poetry doesn’t give evil a pass, it isn’t perfume meant to cover up the stink of lies: that’s sentimentality, another form of vulgarity. Real poetry makes sure that evil doesn’t have the last word, it is the epitome of hope, a reminder that what is true will always prevail. In times like these, poetry is a decision that we make. The irony is, despite the human rights violations that lie at the bedrock of the American experiment, our constitution isn’t just a set of rules and regulations. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States are deeply poetic – just listen to the language. It is a road map if we’re willing to let it guide us back, if we can finally acknowledge to ourselves what is true in this cultural moment: we are lost.

Max S. Gordon is a writer and activist. He has been published in the anthologies Inside Separate Worlds: Life Stories of Young Blacks, Jews and Latinos (University of Michigan Press, 1991), Go the Way Your Blood Beats: An Anthology of African- American Lesbian and Gay Fiction (Henry Holt, 1996). His work has also appeared on openDemocracy, Democratic Underground and Truthout, in Z Magazine, Gay Times, and other progressive online and print magazines in the U.S. and internationally. His essays include “Bill Cosby, Himself, Fame, Narcissism and Sexual Violence”, “Resist Trump: A Survival Guide”, “Family Feud: Jay-Z, Beyoncé and the Desecration of Black Art”, “A Little Respect, Just a Little Bit: On White Feminism and How ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ is Being Weaponized Against Women of Color”, and “Sticks and Stones Will Break Your Bones: On Patriarchy, Cancel Culture and Dave Chappelle.”