In her FPP Interview, Sarah Van Arsdale shares how her current work, a “braided memoir,” has become a “pressure valve” for her “rage and frustration about the crimes the current administration is committing” and how more than ever she feels the need for her writing to “address the mess we’re in.” Hear Van Arsdale read live at “What Just Happened: Writers Respond to Our American Crises” at 6pm this Sunday, November 10th at Silvana in Harlem. Shel’ll be joined by Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, Max S. Gordon, Nara Milanich, Ed Morales and David Tomas Martinez. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Admission is free.

In her FPP Interview, Sarah Van Arsdale shares how her current work, a “braided memoir,” has become a “pressure valve” for her “rage and frustration about the crimes the current administration is committing” and how more than ever she feels the need for her writing to “address the mess we’re in.” Hear Van Arsdale read live at “What Just Happened: Writers Respond to Our American Crises” at 6pm this Sunday, November 10th at Silvana in Harlem. Shel’ll be joined by Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, Max S. Gordon, Nara Milanich, Ed Morales and David Tomas Martinez. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Admission is free.

As a teacher, you’ve shared excellent guidance for writing memoir. You’re currently working on a mosaic memoir about growing up with a family of psychologists and artists in the 1960s that includes watercolor illustrations you’ve painted yourself. Tell us about your mosaic process. What advice would you give to yourself if you were an instructor engaging your work right now?

The mosaic memoir has morphed into being more about our current situation in the USA and less about my childhood. It’s becoming a braided narrative, bringing together strands of becoming guardian to a minor immigrant, our climate catastrophe, and my own experience as an adolescent. The more I worked on it, and the more involved I’ve gotten with immigrant support, the less urgent or relevant my own personal story felt; I’ve been feeling more of a need to have my writing address the mess we’re in.

I’m now calling it a “braided” narrative, a term I learned from the non-fiction writer Ana Maria Spagna, because it moves forward in time; when I was thinking of it as a mosaic, it was more static. I think (I hope!) this makes it a more engaging story. And it now acts as a pressure valve for my rage and frustration about the crimes the current administration is committing.

My advice to myself is to trust the process, to allow the work to shift as my own experience shifts. To allow my life to inform the work, and the work to inform my life. And to not hold back the truth, even when it’s complicated and uncomfortable.

You’ve created a book-length poem called The Catamount that includes your watercolor paintings. What drew you to this animal they say has long been extinct? How did paintings become a part of the work?

I wrote the poem many years ago when I lived in northern Vermont and first heard rumors of this animal, which is a subspecies of mountain lion. There was debate about whether it still existed in northern New England. At the state historical society, there was a file of photos people had sent in, claiming to be of the catamount, and usually being of someone’s ginger tabby. I was drawn to the mystery of the catamount, and to the thought that it could still be roaming the wilder mountain forests; I’m sure it’s a metaphor for the wild places in all of us, the wild creatures that inhabit all of us. When I picked up the poem again a few years ago and fashioned it into a book, everything about the natural world had changed; we’d gone from worry about pollution and forest fragmentation to the global collapse of our environment.

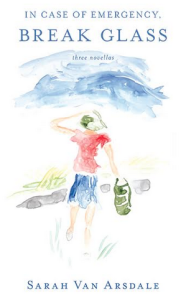

I’ve always drawn and painted; it was part of the fabric of the family I grew up in, with a grandfather who was an illustrator and a mother who was a photographer. It was after publishing my first novels that I started to take my love of painting more seriously. I feel very fortunate to have this additional means of creative expression; it acts as balance to my writing, and since I have very little formal training in it, there’s less pressure on it.

I’ve always drawn and painted; it was part of the fabric of the family I grew up in, with a grandfather who was an illustrator and a mother who was a photographer. It was after publishing my first novels that I started to take my love of painting more seriously. I feel very fortunate to have this additional means of creative expression; it acts as balance to my writing, and since I have very little formal training in it, there’s less pressure on it.

You recently led a writing retreat in Oaxaca, Mexico. You’ve also set fiction in that mythic city. What is it like for you, in 2019, to travel between New York City and Oaxaca, between the fictional and the real?

I’ve spent a lot of time in Mexico, particularly in Oaxaca. When I was a kid we went there, partly to look for pottery as my mother was then working in ceramics. It was a different world then; you were hard-pressed to find the things that were familiar — cereal, or bottled water, or Crest toothpaste. As I’ve continued to spend time there, I’ve seen it become less foreign—at first gradually, and then in the past few years in a sudden rush of American-style coffee shops and “boutique” hotels and expensive clothing stores. Unfortunately, little of this seems to have done much to ameliorate the poverty the people there live with, although there are now more organizations focused on aiding women and children and helping the Oaxacaños gain agency and self-determination.

But the city remains one of the most art-centered places in the world; every few blocks there’s a print-making studio, its doors open to the street, young artists inside creating fabulous art. Artistic creativity is woven into the fabric of life there. My heart sings when I’m there, and I have a kind of longing for Oaxaca, even when I’m there, like Basho did for Kyoto:

Even in Kyoto—

hearing the cuckoo’s cry—

I long for Kyoto.

I started writing the novel decades ago, and it, like my current project, has transformed many times over. When I go there now, I see the streets and storefronts through the eyes of my character, and since the story is set in 2006, I also glimpse the older Oaxaca that persists under the newer, glossier Oaxaca.

You’ve written about frustration you had early in your writing career for being categorized as a lesbian writer. How have those feelings shifted and not shifted over time?

It’s a funny position to be in: I identified as a lesbian much of my early adulthood, and my first novel had a lesbian protagonist, and was hailed as a “crossover” novel, meaning it crossed over from being in the lesbian publishing ghetto to being published by a mainstream press. Now, I’ve been living with a man the past 13 years, so people who meet me now and don’t know my writing assume I’m straight. But I’m still involved in the LGBTQ publishing world, and still carry the knowledge of what it means to identify as “queer” in our world. As the world breaks down stereotypes and categories, such a category seems less important.

What is meaningful action these days? What will tip the scales?

I really wish I knew. I know that I’m planning to do whatever I can to get the current occupant of the White House out next year. Right now I’m about to read “Resist Trump: A Survival Guide” by Max S. Gordon, one of my fellow readers with you on Sunday, and see if he has any tips.

Sarah Van Arsdale is the award-winning author of five books of fiction and poetry. She teaches in the Antioch/LA low-residency MFA program and at NYU, and leads writing workshops in Oaxaca, Mexico and Freeport, Maine. She co-curates the BLOOM reading series in Washington Heights.