In the second FPP Interview with Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés, who is now the director of the Black Studies Program at City College-CUNY, we talk about her earliest religious experiences, how men and women can find freedom, and what she wished she heard as a young academic, among other topics. Come to Silvana on Sunday, February 17th (today!) to hear Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés read with Amanda Alcántara, Tyehimba Jess, and Jacinda Townsend. Admission is free. See you at 6pm!

In the second FPP Interview with Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés, who is now the director of the Black Studies Program at City College-CUNY, we talk about her earliest religious experiences, how men and women can find freedom, and what she wished she heard as a young academic, among other topics. Come to Silvana on Sunday, February 17th (today!) to hear Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés read with Amanda Alcántara, Tyehimba Jess, and Jacinda Townsend. Admission is free. See you at 6pm!

In your book Oshun’s Daughters: The Search for Womanhood in America, you examine African religious practices as represented in creative works of Black women of the diaspora. Could you tell us about your first encounters with religion and spirituality? What inspired you to start researching connections between women’s lives, religious practice, and stories told? I grew up Catholic: I attended Catholic schools from first grade to twelfth grade, and participated in Mass as a singer in choir from fifth grade onward and as a reader from seventh grade. I remember my mother teaching me the “Our Father” as a child, and then begin shocked that everybody knew the words when we went to the first Christmas Mass I remember. Religion, and ritual, have been with me from then; the break for me with the Catholic Church began when I realized I could not ascend its hierarchy, that the only place for me would be as a nun. I had begun participating as a singer and as a reader in order to stop boredom that would encroach when I was listening to a priest drone on.

In your book Oshun’s Daughters: The Search for Womanhood in America, you examine African religious practices as represented in creative works of Black women of the diaspora. Could you tell us about your first encounters with religion and spirituality? What inspired you to start researching connections between women’s lives, religious practice, and stories told? I grew up Catholic: I attended Catholic schools from first grade to twelfth grade, and participated in Mass as a singer in choir from fifth grade onward and as a reader from seventh grade. I remember my mother teaching me the “Our Father” as a child, and then begin shocked that everybody knew the words when we went to the first Christmas Mass I remember. Religion, and ritual, have been with me from then; the break for me with the Catholic Church began when I realized I could not ascend its hierarchy, that the only place for me would be as a nun. I had begun participating as a singer and as a reader in order to stop boredom that would encroach when I was listening to a priest drone on.

When I went to college, I stopped singing – and had a miserable time. When I returned my second year, I quickly joined the Gospel Choir – and I felt better again, and understood how intimately I needed prayer in my life, particularly when it was in the form of singing. That was also when I understood the need for developing my spiritual life – for me, while there is some sense of comfort in Catholic ritual, it’s more a sense of muscle memory than it is actual nurturance.

In Gospel Choir I read the Bible for myself, and developed a relationship with it myself; and then began reading mystical texts from other traditions. In graduate school, I wrote a dissertation that reflected my grappling with womanhood and what it would mean for me, what kind of woman I wanted to be, in this society, at this time. Oshun’s Daughters grows out of that – literally I had begun noticing the invocations to nature that these women writers across the hemisphere were doing, and then paid more attention and understood that they were invoking a whole spiritual system that remains outside of Christian understandings of the world, one that would make so much sense to me, to my upbringing as a woman of African descent born to Puerto Rican parents in New York City. These spiritual systems – Lucumí, Vodou, Espiritismo, Obeah, Roots work, Juju – may not be available for public discussion, and yet they have undergirded our Black communities across the hemisphere for centuries, have ensured our survival.

What do these stories teach us about women and resistance? So much knowledge comes from that which cannot be quantified sometimes. Spirit defies logic, defies Descartes’s maxim, I think therefore I am. What if I feel? And I depend on that feeling, that intuition, to guide me? This means trusting myself, my deepest instincts, my needs and wants – all of which goes against a socialization that dictates that women should put everyone ahead of themselves. What does privileging myself mean? And how does that translate to how I care for those around me, for the community I create? These stories show women facing and negotiating with all of those questions.

Where can women find freedom? Where can men? Both women and men can find freedom in spirit, in love, in light, in each other – it’s something that needs to be actively sought after and cultivated, in a society that seems determined to continue breaking us, mentally, physically, spiritually, emotionally. There are the political realities with which we all live – this administration continues in the tradition of the worst that this country offers, in terms of its genocidal impulse, its misogyny and homophobia and transphobia. Words related to racism and systemic racism continue to lose power, as those who offer sustained critique about how all these hatreds work together get lost in the overwhelming noise of the denials and misdirections about who’s a racist, what’s a racist. So we have to dare to love, to allow ourselves moments of joy, to seek peace, to celebrate ourselves and each other, to be grateful for all that is beautiful and positive in our lives. That is our humanity. This country is literally built on reducing all of us to rubble, to dust, to render us machinery to be disposed of – we resist in our everyday insistence on living, in making mistakes and correcting them, asking for and finding forgiveness, in making space for each other, in encouraging each other, giving each other permission to live in the best way we each know how, teaching, learning, together.

What is your language of tenderness? Does this change? I love this question. I try, in every space I enter, to move in love as best I can. Love as praxis. While we often focus in on romantic love when we use that word, I mean everything that comes with it: kindness, gentleness, empathy. Gratitude. Being grateful for someone holding the door open for you – or someone waiving the dollar fine at the library. I smile, and laugh, a great deal, and try as best I can to stay in peace, grounded in myself, in my body. The older I’ve gotten, I realize that I give gifts to people I care about, just cause – it doesn’t have to be anything big, but something that expresses my appreciation for that person. In all realms of my life, I want to make sure I hear people who cross my path, make sure to communicate that I’ve seen and heard them. I don’t always succeed, but I make a valiant effort. Finally, I talk and write words of tenderness – I try to, anyway (smiling).

When did you know you must learn Portuguese? This happened in graduate school – I knew I wanted to be a Latin Americanist rather than a Peninsularist (these were the two large specialties if you were studying Spanish. And I had the good fortune of meeting Earl E. Fitz at Vanderbilt, who said that if I was going to study Latin America that I needed to learn about Brazil in addition to the rest of the continent. Cacilda Rêgo, a carioca who had just finished her dissertation, spoke a Portuguese that sounded like a Caribbean Spanish to my ear – and that was another turning point for me, because I knew that what the regions had in common were large populations of African descent. That began my study of Brazilian literature, history, and culture.

Who is doing interesting research now? I’m really excited by work that I’m blessed to learn about, mostly through social media, quite frankly. Brittney C. Cooper has rightfully gotten attention for her book Eloquent Rage, but her Beyond Respectability is a serious call to action to be more serious in our study of our intellectual Black foremothers. Anne Eller has written a book, We Dream Together, that forces us to reconsider how Dominican history is told, once you shift perspective from the elite living in a capital and pay attention to others around the country, particularly those living closer to the Haitian border. Yomaira Figueroa is doing tremendous work on shifting how we understand Latinx literature and culture by including Equatorial Guinea in the mix as the only country on the African continent colonized by the Spanish, and one about which many people know nothing. I cannot underscore the necessity of Jessica M. Johnson’s work centering the lives and efforts of Black women in freedom struggles in this hemisphere, and the expansiveness of her studies in the digital realm, on Tumbler. Omaris Zamora completed a dissertation and is working on a book emphasizing the role of spirit as an impetus for knowledge production for Black Dominican women, which I’m excited to learn more about. Out on the West Coast Alejandro Villalpando is doing a great deal in making more space for Central American Studies and the afro-indigenous realities of the region – a space which we ignored when I was in graduate school. April J. Mayes continues to do important work honoring Dominican and Haitian history and activism, and is a leader in thinking of the island of Hispaniola transnationally. Closer to home, Jorge J. Rodríguez V is writing on the legacies of the Young Lords here in the New York City. There’s such amazing work out there being created, I’m looking forward to learning more from them.

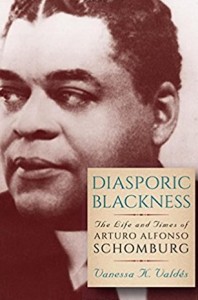

You’ve recently been named director of the Black Studies Program at City College – CUNY. Tell us about your vision. Two years ago now SUNY Press published my book about Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a man who, among many things, wrote an essay called “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” which has been interpreted by many to be a call for the creation of Black Studies as an academic discipline. I am humbled by the opportunity to carry out this call at The City College of New York, a school that was already the university on the hill in Schomburg’s time and in his neighborhood. More than anything, I want to center our students and assist them in reaching their primary goal of graduating; I want to make that process easier by highlighting all that our school has to offer, i.e. scholarships and fellowships and opportunities that many think are beyond them because they come from working class backgrounds. I want to celebrate our faculty who put in long hours in not only teaching our students but also in mentoring and guiding them, showing them what is possible. And I want to strengthen the school’s relationship with Harlem by bringing attention to the collaborations that already exist between our students and our faculty and all of the Harlems that surround us, river to river, and also by creating programs with our community partners.

You’ve recently been named director of the Black Studies Program at City College – CUNY. Tell us about your vision. Two years ago now SUNY Press published my book about Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a man who, among many things, wrote an essay called “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” which has been interpreted by many to be a call for the creation of Black Studies as an academic discipline. I am humbled by the opportunity to carry out this call at The City College of New York, a school that was already the university on the hill in Schomburg’s time and in his neighborhood. More than anything, I want to center our students and assist them in reaching their primary goal of graduating; I want to make that process easier by highlighting all that our school has to offer, i.e. scholarships and fellowships and opportunities that many think are beyond them because they come from working class backgrounds. I want to celebrate our faculty who put in long hours in not only teaching our students but also in mentoring and guiding them, showing them what is possible. And I want to strengthen the school’s relationship with Harlem by bringing attention to the collaborations that already exist between our students and our faculty and all of the Harlems that surround us, river to river, and also by creating programs with our community partners.

I recently heard Brazilian civil rights activist Luana Génot speak of encountering Black Americans who didn’t immediately see the value of engaging across countries, that there’s too many problems here to contend with, but she countered that we can learn from one another. Do you ever encounter these kinds of attitudes inside or outside of the academy, and if so, how do you respond? I was trained hemispherically, meaning that in my research, I am attending to the details of lives and cultures of more than one geographical site in this hemisphere. This is why the word “diaspora” comes up so often in my work, because our narratives – of migration, exile, enslavement – they bypass national boundaries. Before any nation in this hemisphere claimed us, we were African and of African descent. I recently gave a session at the Schomburg for the Junior Scholars’ 2019 Black Teen Lives Matter – and there I highlighted our long Black histories of activism in Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Chile, with mentions of Argentina, Uruguay, Puerto Rico, and Spain. Looking beyond the frames of nation-state allows you to see the similarities of how white supremacy works, and also our histories of dealing with it. We have been here a very long time – this too, all of this, is America.

What words does every young academic of color need to hear? What words did you wish you heard when you started your first research? Find your peoples. Find the people who love you, no matter what — irrespective of what you got on that paper, the hours you’re spending in the library, in the lab. Hold on to them tightly – tell them they mean something to you. Pay attention to those who see more in you than you see in yourself and trust their words. Try to lower the volume on your own fears and doubts and at least look at the path that they are highlighting for you. Celebrate every. single. thing you finish – read that article? A moment’s joy. Underlined something? Prepped that class? Finished that abstract? Submitted it? Dance! Breathe. Take a moment. REST. You are doing this! Focus on all that you are doing and not the list that still needs to get done. Focus on your own abundance. Take care of yourself – if you have to go to therapy, do that. Talk to someone. There’s no shame in this. Don’t feel guilty for being human – for wanting love, sex, to grieve, to feel. Please be happy. It is possible. Be good to yourself, and when you have a chance, pass the baton to the ones coming up behind you.