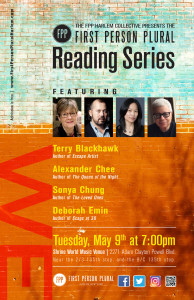

FPP spoke via email with author Alexander Chee whose recent novel The Queen of the Night is a national bestseller. We spoke of what fame meant for his maverick female protagonist, what kind of community can be created at literary readings and via social media, and life in his Sugar Hill sublet back in 1996. Read Chee’s interview then plan to hear him read on Tuesday, May 9th, with Terry Blackhawk, Sonya Chung, and Deborah Emin at Shrine World Music Venue (2271 Adam Clayton Powell between 133rd and 134th streets) in Harlem.

FPP spoke via email with author Alexander Chee whose recent novel The Queen of the Night is a national bestseller. We spoke of what fame meant for his maverick female protagonist, what kind of community can be created at literary readings and via social media, and life in his Sugar Hill sublet back in 1996. Read Chee’s interview then plan to hear him read on Tuesday, May 9th, with Terry Blackhawk, Sonya Chung, and Deborah Emin at Shrine World Music Venue (2271 Adam Clayton Powell between 133rd and 134th streets) in Harlem.

Your latest book, The Queen of the Night, is a historically rich novel that tells the story of an American orphan turned courtesan turned opera singer in 19th-century France. You’ve mentioned that feminism informs the book. Can you talk about your choice to write a female protagonist, and to show a kind of “survivor’s feminism” through Lilliet’s story?

The novel is the result of a kind of feeling I followed, first to this character and then to the life I thought Lilliet, my main character, would lead. I was drawn by the apparent freedoms women like her had then–as celebrities–freedoms that approximated those given to men, but which mostly vanished as their fame did. The result being that their fame was this atmosphere that they manufactured to live inside of, through intense work, self-sacrifice, self-defense, even crime, petty or deadly, and inside of which they survived “at any cost”–a phrase which glosses over what that means, I think, all too often. There’s something Katie Roiphe has called A Stylish Woman Adrift novel–Renata Adler, Joan Didion, Jean Rhys–that I meant to unpack. Those women are describing the problem of being a woman and expecting to be treated as human, and instead being treated as a woman. That all comes from somewhere and that was part of what I was after, the root of that.

The novel is the result of a kind of feeling I followed, first to this character and then to the life I thought Lilliet, my main character, would lead. I was drawn by the apparent freedoms women like her had then–as celebrities–freedoms that approximated those given to men, but which mostly vanished as their fame did. The result being that their fame was this atmosphere that they manufactured to live inside of, through intense work, self-sacrifice, self-defense, even crime, petty or deadly, and inside of which they survived “at any cost”–a phrase which glosses over what that means, I think, all too often. There’s something Katie Roiphe has called A Stylish Woman Adrift novel–Renata Adler, Joan Didion, Jean Rhys–that I meant to unpack. Those women are describing the problem of being a woman and expecting to be treated as human, and instead being treated as a woman. That all comes from somewhere and that was part of what I was after, the root of that.

So George Sand, for example, who influenced a generation of writers during her lifetime, was the first woman to divorce in France and she did so to be a writer. The decision to include things like Sand’s idea of the New Woman, then, was pretty natural to me, and followed out of my opera singer heroine being taught voice by Pauline Viardot-Garcia, Sand’s good friend–the first woman director of the Conservatoire in Paris and one of the first women opera composers. I set out to imagine being someone who didn’t even know they wanted to be like these women, and meeting them for the first time. I rooted Lilliet, and her adventures, here.

You write Lilliet’s story from the first person singular point of view. Even so, was there a sort of collective “we,” a collective feminist identity, that you felt you tapped into for this novel (for example, by reading the work of other female courtesans, such as Celeste Mogador)? If so, how did this “we” manifest in your thinking about the novel?

I wouldn’t say that exactly, because it’s hard to explain how alone these women were then. Lilliet, my narrator, passes through a series of women who act as her teachers in her pursuit of the freedom she feels sure she must be able to find and which is never offered. A freedom she decides to take for herself. I did read extensively into the lives of women of the period in pursuit of this story, though, and populated the novel with some of the real women I found. So there are these tiny biographies inside the novel as a result. My acknowledgements page has details for the interested.

You’re savvy online, and a particularly effective Twitter user. You once tweeted that a lot of writers are on Twitter because “–surprise– text-based communication is fun for writers… Writers have traditionally published their notes, diaries, letters, marginalia, juvenalia–social media is only different in format.” Do Twitter, and social media more generally, provide you with a sense of literary community? How do you manage the balance between the stimulation, outlet, and inspiration that social media can provide, and the over-saturation that can also occur when one spends a lot of time online?

I live in a rhythm with it that I think is like the one most people do, but with accommodations to being a writer. Twitter to me feels like text messaging the world. Instagram is like my visual diary. Facebook is a wedding toast contest–I don’t like it much–or a bulletin board. But I’m always manufacturing a story that is the story of doing my work, a kind of live action literary autobiography/biography, even as I participate in what I see as a community, or communities, really, of supporting writers–friends and colleagues from all over the world. And these communities are really what I love about this most. Nerds who photograph a favorite quote, complain about their process, or just talk books. And I’m on it for the book recs, basically.

We don’t live so much in the world where writers struggle with whether to be on social media anymore. I think we live in the world now where people are on social media, and then they become writers. And if you don’t know how social media works, increasingly, I think you don’t know how people live, and I think you’d have a hard time writing about their lives.

On the other hand, you mentioned, in the 10 Minute Writer’s Workshop Podcast, that you can’t stand emails, because of their never-ending treadmill-like nature. How do you deal with this as a writer? For example, do you limit the amount of time each day you spend answering/writing emails?

John Freeman has written about email as the task list you don’t choose and that’s just so true for me. Melissa Febos wrote a great column at Catapult about the importance of being a little unreliable on email and I think that’s healthy. The problem becomes when you’re like me and you have potentially hundreds of people relying on you professionally, former students and editors, and so you can’t flake out much. So I just try to schedule everything. Emails at this time and never this time, writing at this time, reading at this time, walks and exercise at this time, class at this time, conferences at this time, cocktails at this time, food at this time and sleep at this time, etc. And while a friend has used Google invites for setting dates for sex, I haven’t done that yet. But we’ll see.

You curated your own reading series: Dear Reader, at the Ace Hotel in New York. What can a reading series offer to the community—both the literary and the expanded/public community—that other forms of literary engagement, and online communication, cannot?

When I curate a series I am not picking writers, to my mind, as much as I am putting communities into conversation. With the Ace Dear Reader series, each year I tried to paint a picture of New York. The first year was a way to honor the different literary communities of the city. The second was about Who Belongs, and featured a mix of writers of color, queer, immigrant, refugee and native New York writers. I also always want to show that you can have a kind of programming that went past token gestures toward diversity–too often diversity means white majority with one of each “other kind”. I want to have more than one of each, as it were. Ace was very supportive of this, and we had fun. Great work happened in those hotel rooms. Still does.

You’ve taught at Columbia University in Harlem, and lived many years in Manhattan. What are your experiences with, and what is your relationship to, Harlem? Can you describe your experiences, impressions, sights, of this neighborhood?

I lived in Harlem, Sugar Hill, near 145th and Amsterdam, back in 1996, in a sublet that lasted three months. I was a steakhouse waiter working on my first novel and the rent was 200 a month for my room. It was a hot summer and we kept the windows open for the breeze as we didn’t have AC, and clothes at home were sometimes a burden. I remember the neighbors who never drew their shades, a kind of night theater of nonchalance in the heat. I also remember finding out not everyone was like this–and accidentally flashing a neighbor who kept her shade closed toward me after. I felt guilty about this until I left. Some windows are closer than others.

Back then I kept moving every month or three months, my things mostly in storage, as I worked to earn a deposit on a place of my own, and I lived up and down the island and in Brooklyn as I did so. That period of moves was my education in how the city works. A lot of my friends live in Harlem now, and I love going up to see them, and to see what’s new and what’s the same. Harlem is one of the neighborhoods where New York still feels like New York to me. So I’m grateful whenever I go–and I very much looking forward to the reading.