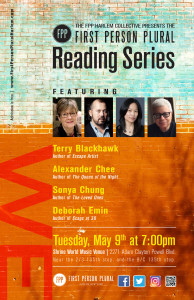

FPP spoke via email with author, activist, and publisher Deborah Emin. She founded Sullivan Street Press and is the creator of the Scags series whose compelling female protagonist copes with family challenges, love, sexual identity, and resistance politics in America. Hear Deborah Emin read with Terry Blackhawk, Alexander Chee, and Sonya Chung at the FPP Season Finale at Shrine in Harlem on May 9th!

FPP spoke via email with author, activist, and publisher Deborah Emin. She founded Sullivan Street Press and is the creator of the Scags series whose compelling female protagonist copes with family challenges, love, sexual identity, and resistance politics in America. Hear Deborah Emin read with Terry Blackhawk, Alexander Chee, and Sonya Chung at the FPP Season Finale at Shrine in Harlem on May 9th!

Tell us more about the Scags series – how did Scags at 7 come about? Did you know from the beginning that this would be a series?

The character Scags came to me on a ride on the LIRR. I watched her and Pops talking, enjoying being together. He sat with Scags in the middle of the day wearing a white shirt, sleeves rolled up, more casual than most “dads” that time of day. Scags was her irrepressible self, enjoying being with him. By the time I got home, I knew I had found the novel I needed to write. I slept on it. Got up and wrote the first draft in 2 weeks at night from 10 pm to 4 am with a list of vignette titles to guide my writing each night.

By the time I began revising the novel, I knew it was part of a series. I knew she would tell her story in a variety of first-person formats (diary, letters, memoir).

Tell us about Sullivan Street Press. What’s it like to go from writer to publisher – and to do both at the same time?

Everyone who writes should study publishing. I fortunately got to live in the publishing world from my first job in NYC. Sullivan Street Press was not my first priority when I became more serious as a writer. It evolved, as things tend to do in my life, out of a need and in this case a need to protect Scags. I had two ideas going in. The first to protect Scags. The second was to change the publishing paradigm. Things were going wrong, had been going wrong and will continue that way until writers, in particular, wake up to the situation.

Being a publisher has always been a form of activism as well as a way to continue to study a topic I love–books and the production of books and their effect on our environment.

I’ve never been good with balancing things. Publishing can take over my life just as writing can. I don’t recommend this joint occupation to anyone unless you have a partner like my wife who understands and forgives.

You have a strong history of advocacy and community-building. How did this become important to you? Can you share a bit about what works, and what you’ve learned?

As with so much of my life, it began in high school. (See below regarding my connection to Harlem.) I had an extraordinary English teacher in my junior year. She ran a tutoring program in Cabrini Green Housing on the South Side of Chicago. Every week, we went there by bus to work with kids who needed help with their schoolwork. Chicago is and was a very racially-divided city. Going from our rather easy life in Skokie to that project gave me a relationship with a young boy, James, whose love of music helped me to help him with his math homework.

This teacher took me with her to lots of things, including a march with Dr. King where I had to be protected, they thought, from the crowds. It was for me an adventure. I did not know what was happening. But when Dr. King was assassinated and Chicago’s South Side blew up, I was more radicalized than with the riots during the Democratic Convention.

I read a lot after that. Everything changes the more you know.

When do you feel most “we”? When do you feel most “I”?

I unfortunately feel too much an “I” in my life. But the “we” always appears in church, when marching with other activists and when I attend a concert, opera or any event whose intention is to join us together. Books do this as well. When they make me feel a part of a whole.

What has Harlem meant to you?

I have a funny story about Harlem. Growing up in Skokie I had one link at first to Harlem, James Baldwin. As I said, I read a great deal so it is no surprise that I’d discover his writings early on. I remember pulling his essay, “The Fire Next Time” and George Bernard Shaw’s story, “The Adventures of the Black Girl in her Search for God” from the library shelves and walking home to read them both. (Sometimes I think Amazon’s algorithms should be modeled on adolescent minds.) I could not say precisely when I gobbled up more of his writings but they implanted a sense of Harlem in me that was not disappointed when I moved to NYC in the late 1970s. The same police racism in the midst of real neighborhoods, just as Baldwin described. Baldwin led me to Langston Hughes. Eventually, in the midst of such cultural barrenness even the voice of Lorca’s, the King of Harlem, gave me an entree that took several years to find its own physical presence in the city. But then one lives here, meaning in this large metropolis, and wanders everywhere, learning everything and filtering a Harlem borne out of Baldwin’s precision and Lorca’s fears. That is not the best way to know a place. But that was my way.

Which writers should we be reading now?

I don’t read much current fiction because I have stupidly downloaded all of Virginia Woolf’s work onto my devices. Given how much she wrote and how much her writing teaches me about writing (and that is why writers must read) I feel compelled to stick mostly with her. Though because I am branching out under Scags’s name to write political thrillers, I am reading those too, again, to study. But in general, I am bad at recommending because my reading habits focus on self-education.

What urgent advice would you give emerging writers?

This final question is important. I believe we need a new nation of storytellers who want to embrace what e-book technology can do. We need writers to both create these new forms and to teach them.

I’m a member of the old tribe. I have ideas and suggestions but have not figured out how to do it. But there is such a deadness, in fiction, as I see it, and I include my work as well, when it comes to exciting forms, engaging adventures. We have seen some examples of people trying to find this new way. Cloud Atlas comes to mind as does David Chowes’s book. But there is something that needs to happen, to explode us out of our stuck-in-a-rut way of telling stories to match both the possibilities of change on a dying planet and to mobilize more people to feel that sense of “we” when they read.

If we could find those writers and support their work, that would be the real test of our faith in books. And if a writer starting out can see that way forward, then please step up. We need you.