While many people flee New York City once June arrives, rising temperatures make me sentimental. Excursions to Jones Beach and ferry rides remind me of spending summer vacations in the city with my grandparents, who spent most of their life together in the area now known as South Jamaica, Queens. To teach us more about the history of his beloved city, my grandfather made adventures out of our daytrips to the Barnes & Noble on 18th St. and Fifth Avenue; South Street Seaport to watch Operation Sail; and Harlem, where he was born and raised.

While many people flee New York City once June arrives, rising temperatures make me sentimental. Excursions to Jones Beach and ferry rides remind me of spending summer vacations in the city with my grandparents, who spent most of their life together in the area now known as South Jamaica, Queens. To teach us more about the history of his beloved city, my grandfather made adventures out of our daytrips to the Barnes & Noble on 18th St. and Fifth Avenue; South Street Seaport to watch Operation Sail; and Harlem, where he was born and raised.

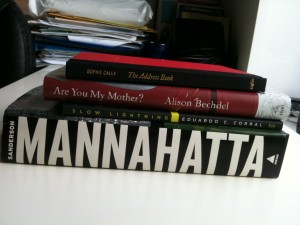

There is a line in The Great Gatsby that refers to New York as “the fresh, green breast of the new world,” and I hear it in my head whenever I look up the Hudson from the top of Riverside Park. This view inspired me to pick up Manahatta: A Natural History of New YorkCity, by Eric W. Sanderson. The book provides an ecological history of the island through narrative and maps that attempt to reveal what the island looked like before the first settlers arrived in 1609. The project envisions native plant and animal life within neighborhoods as we now know them, in addition to those that might have come to be a part of the city through commerce and traffic. Manahatta offers an imaginative history bolstered by computational geography that helps us to imagine how the island’s future might better reflect its verdant past.

Also on my list for the season is Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?, a follow up to her 2006 groundbreaking novel Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Bechdel’s first book focused on her relationship with her father, an undertaker who was closeted and deeply repressed. The trauma of his sudden and perhaps self-inflicted death led Bechdel to want to know more about his life. Are You My Mother? attempts to tell her mother’s side of the story, shifting from her point of view to Bechdel’s growing interest in the history of psychoanalysis. It’s an account of a mother and daughter trying to connect with one another despite a fundamental inability to understand each other. Reviews on this book have been mixed, but I suspect part of the reason for this is that its integration of personal and psychoanalytic history makes it a very ambitious book. I like that.

A couple of weeks ago I caught the tail end of Eduardo Corral’s New York book party for his Yale Younger Poets’s winning collection, Slow Lightning. The reading was over, the wine and cheese were nearly gone, but most disappointing was the fact that the book was sold out! Fortunately I have been able to pick one up in a local bookstore. One of the reasons I am so excited about reading Corral is his well-known affection of the work of Robert Hayden, who is one of the most underappreciated poets of his generation. In a recent interview, Corral explained that Hayden’s work taught him to think about form as an principal aspect of a poem: “My background and my beliefs will pulse through my lines, but the poem has to exist without me, it has to breathe on its own.” I am interested to see how Corral’s deals with form, whether it is through imitation or reinvention—and how he manages this, at times, with a sense of humor. Consider the opening lines to “In Colorado My Father Scoured and Stacked Dishes,” published in the April issue of Poetry: “In a Tex-Mex restaurant. His co-workers,/ unable to utter his name, renamed him Jalapeño.” I can’t get that line out of my head.

I received an advance copy of Sophie Calle’s The Address Book, which was originally published in 1983. The book is a record of interactions that followed Calle finding an address book in the street. In an attempt to get to know its owner without meeting him, she contacted the persons listed in the book and asked them for a meeting where she would ask them a series of questions. I am particularly intrigued by the idea of comprehending a person through his or her associations, and I am fascinated by Calle’s ability to magnify the ways in which exposing our intimate connections poses a risk to our identity.

I received an advance copy of Sophie Calle’s The Address Book, which was originally published in 1983. The book is a record of interactions that followed Calle finding an address book in the street. In an attempt to get to know its owner without meeting him, she contacted the persons listed in the book and asked them for a meeting where she would ask them a series of questions. I am particularly intrigued by the idea of comprehending a person through his or her associations, and I am fascinated by Calle’s ability to magnify the ways in which exposing our intimate connections poses a risk to our identity.

The other re-release I am looking forward to reading is Fran Ross’s Oreo. First published in 1974, the book was practically ignored by audiences and critics. With a new forward written by vanguard poet Harryette Mullen, it has been republished by University Press of New England. A young woman is born to a Jewish father and black mother who divorce early in her life. She comes to New York to find her father, Sam Schwartz. But there are so many Sam Schwartzes in the phone book that her quest takes a turn to the absurd. A few critics have said it was the funniest book they have ever read. Others have said it remains ahead of its time. Either way, it sounds like a great read.

–Wendy S. Walters